Introduction:

The Prahran City Band, under the veteran conductor, E. T. Code, next took the stand. This band showed a wise departure in abandoning the old-fashioned circle and forming in a half-moon, and consequently, every man was facing his leader, and no one was nearer the judge than his neighbour. This method is an improvement and should be adopted by all bandsmen, and a better balance of tone will be accomplished. (“BRASS BAND CONTESTS.,” 1911)

So said a knowledgeable observer from Bendigo who was visiting the Ballarat and listening to the 1911 Royal South Street Eisteddfod band sections. Obviously, he noticed a distinct difference in the sound of the Prahran City Band as opposed to bands that mounted the platform and stood in a circle with the conductor in the middle. Granted, this was in 1911, so the wording is interesting. Bands standing in circles for certain performances was the status quo then. Old fashioned? Possibly. However, as with anything in the band movement, any significant change took time, and Australian bands generally followed developments from England. Is it ironic that the status quo was shaken up by an Australian brass band visiting England? There is more to that story.

Playing within the confines of band rotundas and on the elevated platforms used at band contests meant that bands performed in all sorts of shapes – circles, squares, the half-moon (thanks to Prahran City Band), and other formations. As a historical curiosity in the band movement, these formations bring the question of why because even though some unusual formations are necessary in modern times, in general, brass bands now perform in a generic formation wherever possible.

This post is about band formations mainly in outdoor settings, although some might say this applies to indoor performances as well. Unfortunately, there is a lack of written information about the specifics of early brass band formations for performances – no one has written a manual (apart from marching). Much of what can be discussed comes from the anecdotal evidence of photographs and the odd review of contests. The assumption then can be made that when bands formed up on elevated platforms and in band rotundas, formations were dictated by the platform’s shape and the conductor’s discretion.

Elevation:

One common element that has stood the test of time is the elevation of a musical ensemble for performances. A stage or platform tends to mean that bands (and orchestras, choirs, etc.) are better heard and seen by the audience. The Kalgoorlie Miner newspaper noted as such when reviewing a performance by the A.W.A. Brass Band in September 1903 prior to this band making the long journey to compete in Ballarat.

The advantages of an elevated position for band performers in submitting their programmes to the judgement of the public was made abundantly manifest at the Boulder Recreation Reserve last night when the various items in the bill were given from a temporary rotunda or covered-in platform, erected by the Boulder Orchestral society, to facilitate the object of the gathering last evening, and also for use when the members of that particular organisation take up the running in the absence of local bands at the Ballarat competitions. The players were not hemmed in and incommoded by spectators, and the music was conveyed with better effect. (“THE A.W.A. BRASS BAND.,” 1903)

Bands had also noted the advantages of band rotundas and bandstands, and the visit of the Besses o’ th’ Barn Band to Victoria was a catalyst for further work (de Korte, 2021). According to an article published in The Age newspaper in October 1907, Code’s Brass Band lamented the lack of facilities for performances.

It was mentioned that the great enthusiasm aroused by the playing of the Besses o’ th’ Barn Band should have the effect of showing the authorities that good band music is appreciated by the general public, and drawing their attention to the lack of facilities in Melbourne for bands to give open air performances. What is badly needed is the erection of suitable rotundas or band stands in public parks and reserves. At present when a band gives an open air performance, an unsightly temporary stand must be erected, or they must play standing on the grass, a proceeding not at all satisfactory either to the musicians or their audiences. (“CODE’S BRASS BAND.,” 1907)

Band Rotundas:

Band rotundas, by nature of design, were largely elevated structures, some more than others. Rotundas are also a classic example of where the structure somewhat dictated how a band was arranged. Older band rotundas in Australia were often designed in an octagon with the central performance area occupied with a ring of music stands and space for the conductor in the middle. Whenever a rotunda was opened in a locality, it was a special occasion as it meant the local band had a proper performance space, as this article published in The Daily Telegraph newspaper about the new structure constructed by the Newtown Brass Band shows.

A desire having been expressed that it should give more frequent public performances, arrangements have been made for it to play every week in one of the local parks – Victoria Park, Marrickville, and Erskineville. Hitherto the band has suffered under a great disadvantage when playing in the open by not having a proper stand. The result was that the players were liable to be encroached upon by the crowd, causing much inconvenience, whilst the music was not heard at its best. The attempts to get a stand provided for them having failed, the members, who included several tradesmen, set about constructing one of their own. They did all the work themselves, the only cost being that of the materials. They have succeeded in producing a structure admirably adapted for its purpose. It is octagonal in shape and will accommodate about 40 performers. It can be taken to pieces without much trouble, and removed on one day, the work of fixing it up occupying only about a quarter of an hour. There is an outer platform, on which the players will stand, uprights carrying supports for the music, whilst the conductor, from a smaller stand in the centre, has everything under his control. (“NEWTOWN BRASS BAND.,” 1904)

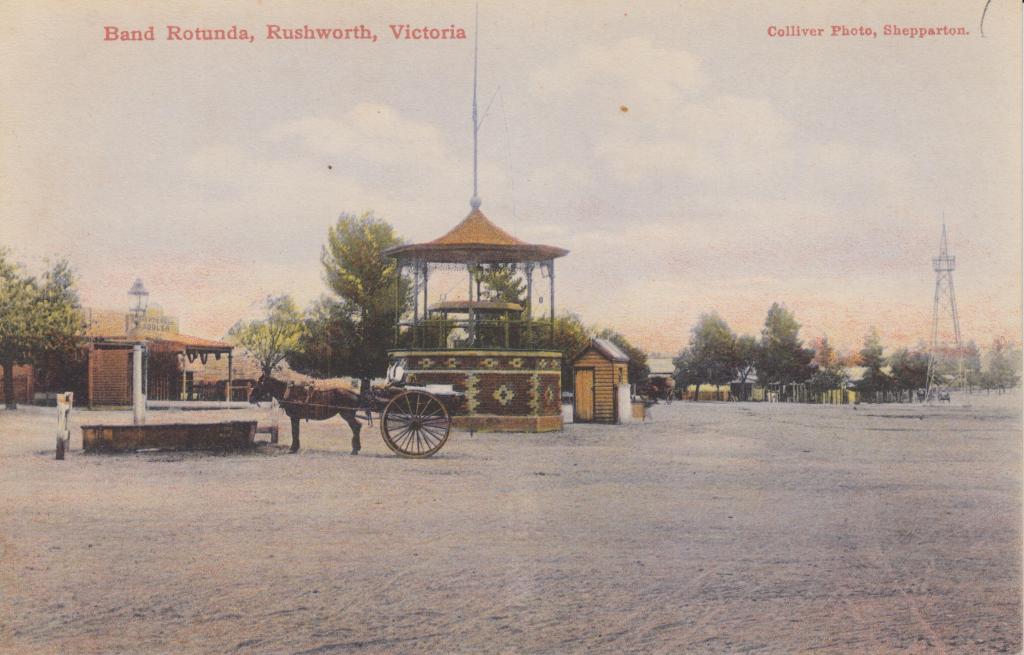

The band rotunda at Rushworth in northern Victoria is an example of this style of design. Below is a postcard dating from 1907 and a later photograph of the rotunda – thankfully, the ring of music stands has not been removed over a century later (de Korte, 2024c).

(The photograph was taken by Jeremy de Korte, 26/05/2024)

It can be seen that this particular rotunda is a bit on the small size, and when visiting the town, this author was told by townspeople that the current Rushworth and District Concert Band does not play up on this rotunda at present due to space constraints. As with any structure of this type, they are of all different sizes and designs. Images of band rotundas from all over Australia can be viewed on the companion blog, Australian Band Stands: Iconic structures in towns and cities.

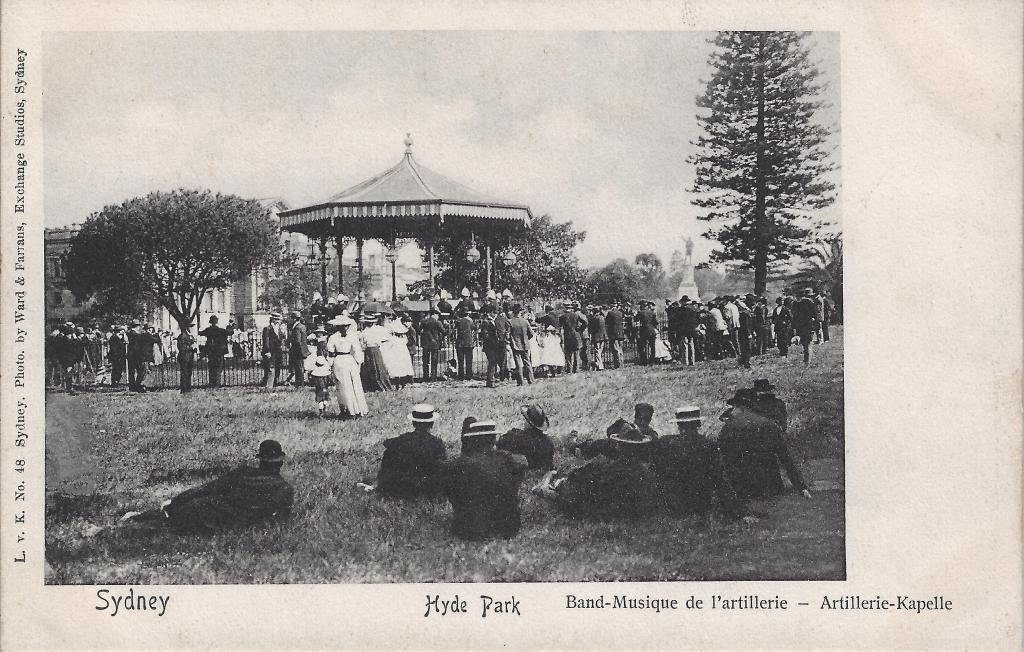

What a band might have experienced when playing on a rotunda like this can be viewed below where we can see the New South Wales Artillery Band playing at the Hyde Park Rotunda. The band members can just be seen standing around the edges of the rotunda facing inwards towards the conductor.

Platforms:

Bands playing on temporary platforms was quite common, and again, still is to a certain extent. Like playing on rotundas, platforms tended to dictate the shape in which a band performed. Circles and rectangles tended to be the norm, but as the Prahan City Band demonstrated, other formations were used (“BRASS BAND CONTESTS.,” 1911). Perhaps the Collingwood Citizens’ Band, seen in the photograph at the head of this post, was rehearsing in a circle in preparation for a contest.

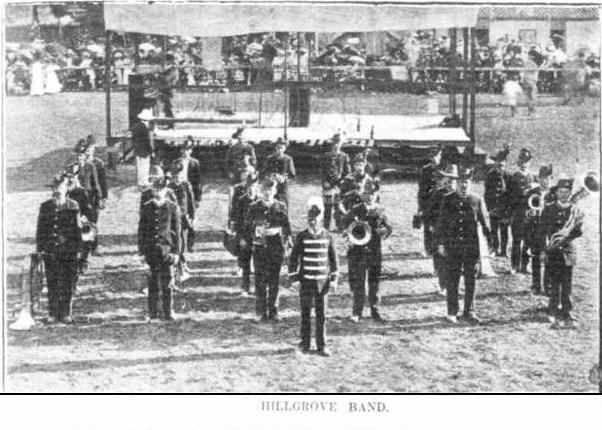

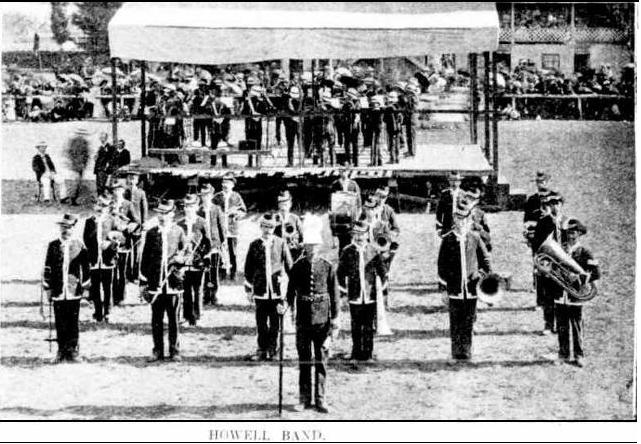

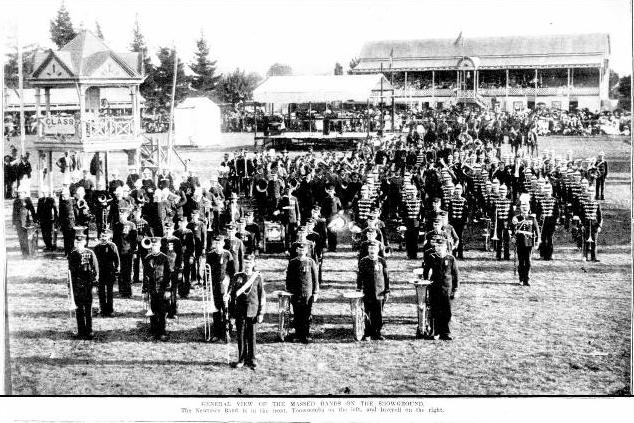

Thankfully, there are some newspaper articles and photographs that show bands performing on an elevated platform at a contest. The series of photographs below taken at the Inverell (N.S.W.) Musical Festival in 1907 and published in The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser newspaper is a perfect example. As we can see, the bands are on the platform formed up in a circle. The temporary platform is in full view, and when each band is getting their photograph taken, the next band is taking their turn on the platform. The photographs are displayed here separately, and the photograph of the massed bands has also been included.

The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 10/04/1907, p. 925

The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 10/04/1907, p. 925

The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 10/04/1907, p. 925

The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 10/04/1907, p. 925

The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 10/04/1907, p. 925

Likewise, the 1911 Kalgoorlie Brass Band Competitions and Eisteddfod was well-documented by photographer Mr. R. Vere Scott, and his photos were published in the Kalgoorlie Western Argus newspaper (Scott, 1911b). On a side note, this contest was notable as it not only included some Western Australian bands but also the Broken Hill Band, which made the long journey to Kalgoorlie, as can be read about in a previous post (de Korte, 2019). One of the photographs that Mr. Scott took was of the Boulder City Band taking their turn on the contest platform on the main oval (Scott, 1911a). From looking at this photograph, one wonders how much the audience heard as the band members were all facing the conductor in the middle, and only some of the band members were likely to be pointing their instruments at the audience in the stands.

Elevating an ensemble was important enough for the musicians and the audience. Yet there was the issue of sound production as well. It could be assumed that it was possibly easier to hear a band playing on rotunda due to the roof reflecting sound outwards. But what about a band playing in a shape on a platform? How much of that was heard? Would it be better for a whole band to project outwards, generally in one direction?

1924, the year formations changed:

(Source: IBEW – the History of Brass Bands blog)

Much happened in 1924. The Malvern Tramways Band did not travel to the United Kingdom to compete in the famous English band competitions, as they were widely expected to do (de Korte, 2024a). However, the Newcastle Steel Works Band did travel to England and caused a stir when they got there, mainly for the fact that they won two of the major championships and came third in another major championship (Greaves, 2005). This was in addition to the numerous concerts and other events the band played at to earn some money during the tour – the trip was very expensive (Bythell, 1994; Helme, 2017).

While the Newcastle band astonished the English band aficionados with their playing, they did something else that changed the band world forever; they went on stage at the Belle Vue contest in Manchester – their second contest of the tour – and sat in a concert formation (Greaves, 1996).

Now, admittedly, the band had sat in concert formations at previous concerts in England, but this was the first time the band had sat in this formation at a contest.

Although they had already sat in formation at previous contests, the audience at the King’s Hall were still taken aback when the Newcastle Steel Works players arrived on stage – each carrying a wooden chair. They then proceeded to sit in the now ‘traditional’ formation before Albert Baile took the stage. (Mutum, 2024)

The Australian band historian Jack Greaves (1996) provides us with a more detailed description of the event and the implications of what Newcastle set in motion.

The year 1924 also saw the introduction by the Australian visitors of a new innovation at the Belle Vue contest. Up till then, it was customary for bandsmen to stand in a circle on the contest platform during the entire rendition of the test selection. Tradition was broken by the visitors, however, for when their turn to play came, each man carried on to the platform his own chair and the band then arranged itself into a horseshoe formation. As they were the second last band to play, it meant that each bandsman had the responsibility of retaining possession of his own chair for most of the day, which also meant carrying it about with him wherever he went. From then on, all bands at Belle Vue have played seated.” (pp. 49-50)

There is no record as to which Newcastle band member thought up the new formation, although one would suspect that Conductor Albert Baile was the instigator. Various accounts, however, do mention the band being coached by conductors James Ord Hume and William Rimmer prior to the Belle Vue contest – did they also have an influence? (Bythell, 1994; Greaves, 2005). Interestingly, the hall at the time was one of those arenas where the audience could watch the band from all four sides, so having a band perform on chairs in a concert formation must have been a novelty for them (Helme, 2017). One of the reasons (nominally the weakest reason) the English commentators used to justify Newcastle’s win was the different seating formation (Bythell, 1994).

So yes, it did take an Australian band visiting England to change the seating formation of brass bands. Below are photographs of the Newcastle Steel Works Band and their conductor Albert Baile upon their return to Australia in 1925 as published by The Observer newspaper.

Conclusion:

What is evident from this little story is that evolution in the band world takes time and can happen quite suddenly. This was not a movement that did not copy developments in the orchestral world where orchestras had been sitting in a concert formation for centuries. As can be seen in the photographs from England and Australia, playing on an elevated platform was part of the performance practice. Playing in a shape with the conductor in the middle, which was a part of contests for the best part of three decades was something that could have been changed quite easily. However, for some reason, it was accepted musical practice for the benefit of the conductor, and possibly an adjudicator, but not for an audience sitting at a distance.

We can thank the innovations of the Newcastle Steelworks Band a century ago for changing the playing formations. What they did went from novelty to accepted practice very quickly.

References:

Band Contest, Yallourn. (n.d.). [Photograph]. [phot8000]. The Internet Bandsman Everything Within, Vintage Brass Band Pictures – Australia. http://www.ibew.org.uk/vbbp-oz.html

BRASS BAND CONTESTS : THE BALLARAT COMPETITIONS : A BENDIGONIAN’S IMPRESSIONS. (1911, 31 October). Bendigo Independent (Vic. : 1891 – 1918), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article226819795

Bythell, D. (1994). Class, community, and culture: The case of the brass band in Newcastle. Labour History(67), 144-155. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27509281

CODE’S BRASS BAND. (1907, 11 October). Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954), 9. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article204997427

Collingwood Citizens’ Band rehearsing in a quarry. (1906). [Photograph]. [phot19034]. The Internet Bandsman Everything Within, Vintage Brass Band Pictures – Australia. http://www.ibew.org.uk/vbbp-oz.html

Colliver Photo. (1907). Band Rotunda, Rushworth, Victoria [Postcard]. [194458]. W. T. Pater, Printers and Stationers, Shepparton, Victoria; Melbourne, Victoria.

de Korte, J. D. (2019, 06 September). Trans-continental connections: the brass bands of Broken Hill and Kalgoorlie. Band Blasts from the Past: Anecdotes, Stories and Personalities. https://bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2019/09/06/trans-continental-connections-the-brass-bands-of-broken-hill-and-kalgoorlie/

de Korte, J. D. (2021, 16 February). Influences from Britain: James Ord Hume and “The Besses Effect”. Band Blasts from the Past: Anecdotes, Stories and Personalities. https://bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2021/02/16/influences-from-britain-james-ord-hume-and-the-besses-effect/

de Korte, J. D. (2024a, 28 February). Hype versus reality: why the Malvern Tramways Band never travelled to the United Kingdom. Band Blasts from the Past: Anecdotes, Stories and Personalities. https://bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2024/02/28/hype-versus-reality-why-the-malvern-tramways-band-never-travelled-to-the-united-kingdom/

de Korte, J. D. (2024b). Rushworth, Vic. : Queen Victoria Jubilee Band Rotunda [Photograph]. [IMG_9916]. Jeremy de Korte, Newington, Victoria.

de Korte, J. D. (2024c, 11 April). Rushworth, Victoria – Queen Victoria Jubilee Band Rotunda. Australian Band Stands: Iconic structures in towns and cities. https://australianbandstands.blog/2024/04/11/rushworth-victoria-band-rotunda/

Greaves, J. (1996). The Great Bands of Australia [booklet] [2 sound discs (CD) : digital ; 4 3/4 in. + 1 booklet]. Sydney, N.S.W., Sound Heritage Association Ltd. https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/2372005

Greaves, J. (2005). A musical mission of Empire : the story of the Australian Newcastle Steelworks Band. Peters 4 Printing. https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/3640204

Helme, C. (2017, 23 September). The Newcastle Steelworks Band from Australia and its 1924 visit to the UK. Chris Helme : Sunday Bandstand, 229. http://www.chrishelme-brighouse.org.uk/index.php/sunday-bandstand/bandstand-memories/item/229-the-newcastle-steelworks-band-from-australia-and-its-1924-visit-to-the-uk

Holman, G. (2020, 15 April). The Crystal Palace and bands. IBEW – the History of Brass Bands. https://ibewbrass.wordpress.com/2020/04/15/the-crystal-palace-and-bands/

MUSICAL FESTIVAL AT INVERELL. (1907, 10 April). Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 – 1912), 925. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article165387808

Mutum, T. (2024, 30 August). The day the Open changed forever. 4barsrest, 2067. https://4barsrest.com/articles/2024/2067.asp

NEWTOWN BRASS BAND : OPENING OF A NEW BAND STAND. (1904, 22 April). Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 – 1930), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article237811793

RETURN OF THE CHAMPION NEWCASTLE STEEL WORKS BAND. (1925, 10 January). Observer (Adelaide, SA : 1905 – 1931), 34. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article166315185

Scott, R. V. (1911a, 10 October). BOULDER CITY BAND. Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896 – 1916), 21. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article33398332

Scott, R. V. (1911b, 10 October). KALGOORLIE BRASS BAND COMPETITIONS AND EISTEDDFOD. Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896 – 1916), 21. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article33398332

THE A.W.A. BRASS BAND. (1903, 28 September). Kalgoorlie Miner (WA : 1895 – 1954), 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article88873523

Ward & Farrans Exchange Studios. (n.d.). Sydney : Hyde Park : Band-Musique de l’artillerie – Artillerie-Kapelle [Postcard]. [No. 48]. L. v. K., Sydney, N.S.W.