(Source: Victorian Bands’ League Archives)

Introduction:

There is no doubting that any band requires leadership and that the leaders of bands, whether they be musical – conductors/bandmasters, and Drum Majors – or in administration, require a set of qualities that are different from other band members. This has been the case in our band movement from almost the beginning and many musicians have aspired to be in such leadership roles. Often, they have succeeded. At times, the needs of the band have not been met. There is no doubting that these roles require lots of hard work and skill, not only as a leader but also as a musician.

We will see some criticisms from the great British band adjudicators who nearly always had plenty to say. Of course, we know that many Australian band conductors of the past were very highly regarded, but that fact was sometimes ignored by our British counterparts. However, given this post will touch on some controversial histories of Australia’s band movement, we will probably end up with more questions than answers.

Whatever we do in the band movement has some basis in history and tradition. There are three aspects to this post that will provide some context and history. Firstly, we will see some of the problems that existed in bands regarding musical leadership, mainly seen through the eyes of eminent band personalities. The second part of this post will talk about the interesting status quo of recruiting conductors who just happened to be Cornet players as well. In the third part of this post there will be an examination of possible solutions to musical training and knowledge, which was the cause of much hand wringing for many decades – good intentions were expressed, except many of these good intentions failed to come to fruition.

The problems at hand:

In 1902/03, Scottish band conductor and adjudicator James Ord Hume visited Australia and New Zealand to adjudicate at many Eisteddfods, and through this visit he imparted his knowledge and opinions whenever he had an opportunity. This visit, and his subsequent visit in 1924 were detailed in a previous post (de Korte, 2021). The influence he had on Australian bands, in conjunction with the tours by the Besses o’ th’ Barn Band, was profound and he noted as much when he visited again in 1924. In deference to the topic of this post however, his early impression of Australian bands was that they lacked “tuition”, and this he put down to the knowledge of the conductor – “…here it seems to be ‘Australia for the Australians,’ and that will not do in music at any rate” (“MR. J. ORD HUME.,” 1903). James Ord Hume was noted for the forthright nature of his comments (Thirst, 2006).

Did James Ord Hume have a valid point? He provided comment in 1902/03 when the Australian band movement was essentially at the start of rapid development. Perhaps he was laying a foundation for Australian bands to build on, rather than direct criticism. However, we cannot treat this as a purely isolated observation as other band identities, some of them visitors from the United Kingdom, made similar comments over time. In a wide-ranging interview published in the Australian Star newspaper in 1908, “Mr William Short, chief trumpeter in the private band of King Edward” had plenty to say regarding Australian bands and what conductors should be focusing on (“AUSTRALIAN BANDS,” 1908).

Your bands are badly in need of good tuition. Bands should play like one man. They should be taught by men who have a practical knowledge of the various instruments and a large experience. […] The bands in Australia want polishing up. One or two are really good and the others are mediocre. Teaching is everything. The conductor should insist on having complete charge of the band. He should not let anything slip. Some of the bands I have heard have very much the appearance of being under divided control.

(“AUSTRALIAN BANDS,” 1908)

Now, perhaps this was a little unfair given the times, but again, like the comments from James Ord Hume, not unwarranted and it reflects the leadership situation in the Australian band movement at the time.

It must be noted that the tuition of bandsmen and bandmasters was a pet topic for Mr. Ord Hume and in 1909, an article written for the British Bandsmen magazine was reprinted in The Cairns Post newspaper (Ord Hume, 1909). For the sake of brevity, his words on tuition will not be directly quoted however there are some aspects of his article that are pertinent to the next section – the article can be accessed by the link on the citation.

When James Ord Hume visited Adelaide in October 1924 during his travels across Australia from Ballarat to Western Australia (and then back to England), he was interviewed by The Advertiser newspaper where he made some interesting observations. Generally, he was in praise of the rise in standards. However, he tempered this with some other pointed remarks about bands and conductors.

The chief fault in Australia in the lower sections he found was the lack of proper tuition. However enthusiastic a bandmaster might be, the lack of that particular tuition was keenly felt. Some of the bands in that section he had heard had no interpretative ability whatever. They were very enthusiastic, but were led by bandmasters who themselves should have had better tuition. That was a fault which should be remedied by the associations, which, to the best of his knowledge, did not permit others than bandmasters to train or conduct the bands. […] One band in particular played so poorly that he felt sorry for the bandsmen, who, in his opinion, were led like lost sheep. He felt inclined to go up and ask the bandmaster if he might be permitted to conduct those selections again, even without a rehearsal, to show what the bandsmen could really do. They lacked tuition, and that was the whole trouble.

(“A GREAT BANDMASTER.,” 1924)

Evidently, after James Ord Hume arrived back in England, he made some further remarks in relation to Australian bands, which touched off a war of words, most notably between several South Australian band identities. First was Mr. William Foote, then bandmaster of the Adelaide Tramways Band where he quoted some of Mr. Ord Hume’s words in an article published by The News newspaper in early June 1925. Mr. Foote stated,

It is the truth. In saying that the bands are more advanced than the bandmasters he has put his finger on the root of the trouble.” said Mr. W. H. Foote, A.R.C.M. speaking of the criticism against Australian bands by Lieut. J. Ord Hume.

[…]

“We have the musicians, but we lack the men to direct them.” Mr. Foote concluded. “The ‘painfully correct’ playing of which Lieut. Ord Hume complains is the direct result of the bandmasters’ want of artistry and skill.”

(“BAND CONDUCTORS,” 1925)

Mr. Foote was an ex-military bandsman from England with a high degree of orchestral training and he was brought out to work with the Adelaide Conservatorium and the Adelaide Orchestra. He was appointed conductor of the Adelaide Tramways Band in 1922 upon the resignation of Mr. Christopher Smith (“AN ENTHUSIASTIC MUSICIAN,” 1921; “NEW DIRECTOR FOR TRAMWAYS BAND.,” 1922).

In the same article that quoted Mr. Foote, Mr. W. Levy, then President of the South Australian Band Association (SABA), also supported Mr. Ord Hume’s remarks.

He is correct so far as the conductors are concerned,” he said, “and through there are some fine bandmasters, here there are many who can only bring a band up to a certain standard. […] Lieut. Ord Hume is one of the leading authorities on bands in the world, and his remarks should be treated with respect.

(“BAND CONDUCTORS,” 1925)

Almost immediately there was reaction from another member of the South Australian band community. Two days later, a letter was sent to The News newspaper by Mr. C. J. Madge, bandmaster of the Unley Municipal Band where he was very critical of the attitudes of Mr. Ord Hume, Mr. Foote, and Mr. Levy.

…the latest statement of Mr. Foote, in which he criticises the ability of our present conductors, is an insult to the intelligence of a body of men who are freely giving of their best in the interests of bands in Australia. The painfully correct playing of which Mr. Ord Hume and Mr. Foote complain was the playing that carried the Newcastle Steelworks Band ahead of the best bands that Britain and her conductors could produce. But Mr. Hume went farther, and stated that that there were even better bands in Australian than that at Newcastle. These better bands are conducted by Australian conductors whom Mr. Foote characterises as leading bands which only muddle along.

The remarks of Mr. W. Levy (president of the Bands Association) also call for comment. It is hard to credit that the president of the bands criticises the men who work for practically no or little remuneration. Certainly the conductors can improve, and from what we say of Mr. Ord Hume, while in Adelaide he, too, is not infallible, but it was hardly expected that our president would criticise bandmasters, and thus probably sow the first seeds of dissatisfaction in the bands he professes to cherish.

(Madge, 1925)

The colloquially titled letter writer, ‘Dulcet’ chimed in with a smaller letter published on the same day as Mr. Madge’s letter which suggested that Mr. Ord Hume “adapted his criticisms to suit various audiences” (Dulcet, 1925) – Mr. Ord Hume apparently said one thing in Australia and then upon returning to England he contradicted previous words – which may or may not be true – people had their opinions.

A day later after Mr. Madge’s letter had been published, Mr. W. Levy, wrote his own letter to clarify his previous comments and refute Mr. Madge.

It is not my intention to enter on a newspaper controversy, but I cannot allow to pass unnoticed the comment of Mr. C. J. Madge in regard to myself. When I expressed my opinion respecting Mr. Ord Hume’s remarks on bands and conductors in Australia my intention was not to criticise “the men who work for practically no or little remuneration.” I simply stated a fact as it presents itself to me, and shall indeed be sorry if the opinion expressed “sows the first seed of dissatisfaction in the bands I profess to cherish.

Unfortunately, the truth is hurtful at times, but one must sometimes be “cruel to be kind.” No one more than myself holds conductors and bandsmen in higher regard, or recognizes to the full the amount of hard work and sacrifices entailed by these men. Yet I cannot hide the fact that there are bandmasters who, unfortunately, for the bands concerned, have their limitations. They work hard and conscientiously unto their limit.

(Levy, 1925)

It was all very well and good for Mr. Levy to make these comments in his letter, and to try to clarify his attitudes towards band conductors. There is no doubting that he was trying to do the best he could for the band community. Certainly, Mr. Ord. Hume was a highly respected band authority. Maybe his remarks were taken out of context and misinterpreted by Mr. Foote and Mr. Levy…?

Some days later, another letter from Mr. A. B. Michell, Honorary Secretary of The Mitcham Band was published in The News newspaper where he took apart Mr. Ord Hume’s remarks.

Lieut. J. Ord Hume states that “Australian bands are ahead of their bandmasters,” but he does not say in what particular. Then he declares that “professional conductors are a necessity for the improvement of Australian bands.” This seems ridiculous when the population of Australia is compared to that of Britain. And you can count on ten fingers all the first-class all the first-class English bandmasters.

(Michell, 1925)

…and muddying the waters even more, Mr. Michell wrote,

I was surprised to learn of Mr. Foote supporting the statements of Mr. Hume because on one occasion when I spoke to him of Mr. Ord Hume, Mr. Foote said that he did not know of him in the musical world at home.

(Michell, 1925)

One wonders what the public thought of these exchanges.

In concluding this section, we can see some valid points come across. Firstly, the opinions of renowned bandsmen did not truly reflect or understand the Australian context. No doubt these visiting bandsmen meant well and tried to support the local band movement as best they could, however, their opinions did cause some controversy. Secondly, Australian bandmasters needed proper training to become bandmasters. The bandmasters needed to know more than just conducting, they needed to be musicians and teachers, and this will be partly explored in the next section. Thirdly, it was all very well saying tuition was the key, and the people that said this were probably correct. If tuition is the key, then the solution of setting up training programs is obvious, and it was. Except, as we will see in the third section of this post, that was easier said than done.

The status quo:

WANTED, BANDMASTER, to teach WALCHA BAND. Must be a Cornet Player.Applications close 24/7/’08. H. DOAK, Secretary.

(Doak, 1908)

WANTED, CONTEST BANDMASTER. Cornet-Player preferred. Boulder City Band. Salary £5 per week. We have a good Band, 26 members, full instrumentation. Apply early. JAS. HARRIS, Sec., Box 19, Boulder, W.A.

(Harris, 1910)

Bandmaster / Cornetist:

If we were to read the many articles surrounding the bandmasters of old, we would see some common threads. One thread is that for the smaller bands and mainly country bands, the bandmaster they gained was most often a local music teacher who possibly had some knowledge of brass instruments. Mr. E. H. McKee, newly appointed bandmaster of the Port Macquarie Band in 1919 was a prime example. He was reputed to be able to play almost all instruments and was essentially a teacher of “violin, piano, banjo” (no mention of his brass playing credentials) – however, he was certified from Trinity College London (“New Bandmaster.,” 1919). There were many others like Mr. McKee.

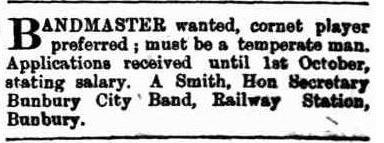

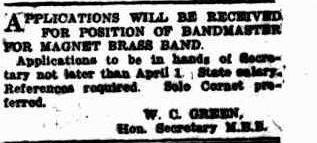

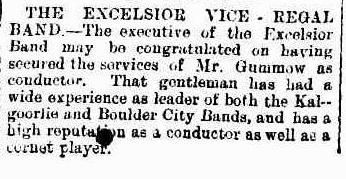

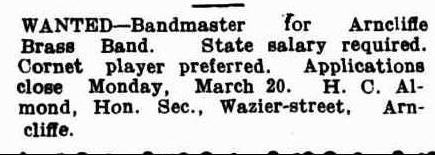

The other common thread was that the bandmaster was a highly credentialed and trained Cornet player that had climbed the ranks of the brass band movement and was then encouraged or assumed the role of bandmaster. Some of them were legendary musicians. One can see by the photo of the Victorian Bandmasters’ Association at the top of this post that these musicians were the very pinnacle of bandsmen. They were also very fine conductors and adjudicators (de Korte, 2020a). So, within the band movement at the time, when it came to the appointing of new bandmasters, the preference was to gain a person who was also a Cornet player – the advertisements of the time which can be viewed through this section attest to this practice.

However, this was problematic, and it drew criticism. In 1908 an article was published in The Age newspaper outlining what it would take to improve band music. The author touched on many aspects, but one that stood out was tuition of bandsmen and bandmasters. There were some quite pointed words.

Our bandsmen, save in some isolated instances, seldom achieve real mastery, not because they lack ability or the necessary perseverance, but because they get too little tuition. What is more hampering, the tuition is not always of the best. Most of it is done by the bandmasters, and these, putting aside one or two who can be credited with good work, are mostly unequal to the task. They are as a rule cornet players, and their proficiency in this respect is supposed to give them the wherewithal to train recruits in the use of the saxhorn, the euphonium, the trombone, and what not.

(“IMPROVEMENT OF BAND MUSIC.,” 1912)

This may have been a very Australian way of doing things (and we can draw from Mr. Ord Hume’s remarks in 1902/03 about just how the Australian band movement tended to have its own way of operating). As mentioned, James Ord Hume wrote a long article for The British Bandsmen in 1909 and the Cairns Post newspaper reprinted this article. It was not specifically directed at Australian bands. Although, we can see in his writing some indirect criticisms that would be applicable to Australian bands as evidently, some English bands were also appointing bandmasters who were Cornet players.

One of the members generally one who can blow a cornet, is the lucky choice as the bandmaster, regardless of his experiences or capability as a teacher, as long as he is good hard blower of the cornet.

[…]

No man appreciates the artistic cornet playing teacher better than I do. I consider that an artiste upon his instrument is the very best instructor. It is not to this class of cornet player I refer to but to the band that is continually advertising for a bandmaster – “cornet player preferred.” Why does this band not advertise honestly for a cornet player and have done with it? It is in such matters as this that ruination gradually comes in. The best instrumentalists are not necessarily the best teachers, and more than the best teachers should be also artists and instrumentalists.

(Ord Hume, 1909)

He wrote further in this article on the problems of tuition (it was one of his favourite topics after all) and there is much to be taken from this article. But this did not end the criticism of the Australian band movement when it came to employing bandmasters. Many years later in 1932, a Mr. Frederick J. Nott, teacher of “organ trumpet, harmony, counterpoint and composition” at the Melbourne Conservatorium was interviewed by The Mercury newspaper when he was holidaying in Hobart in 1932 (“MUSIC AND MUSICIANS,” 1932). He was not a stranger to bands having played in A.I.F. bands and he understood the band movements in Britain and Australia. He had a bit to say about the training and qualifications of Australian band conductors.

Reacting to the suggestion that more musicianly conductors would make a vast different to bands, Mr. Nott said: “Yes, the mistake is often made of appointing a man as bandmaster because he is a good cornet-player. The proper place of such a man is as solo-performer, not as conductor. The ideal conductor is a thoroughly trained musician, and, let me add, he should, if possible, have a practical knowledge of every instrument in the band. A trained musician will not allow those crudities of interpretation to pass that are often heard from bands under the beat of solo-cornetists. […] In Australia on the other hand, a man who can play his cornet with a good tone and fair execution, without being able to explain the simplest problems in theoretical music, is considered a fit person to train and conduct a band. This, of course, is all wrong. It would be far better to get a trained musician as conductor, even if he could not play, as long as he understood the principles and the technique of the instruments.

(“MUSIC AND MUSICIANS,” 1932)

We can see the pattern of what Mr. Nott was describing simply through the many advertisements, so it is no surprise that he was criticising the fact that many band conductors in Australia had gained their position because they were Cornet players who just happened to be bandmasters as well, or vice versa. Bearing in mind that this was some years after the comments from Mr. Ord Hume which is telling; it means that Australian bands were still hidebound by a practice of employing Cornetist-Bandmasters who may or may not have been good musicians. Again, it signifies that training specifically designed for bandmasters was not available at the time, there was no Australian Band & Orchestra Director’s Association for example, nor were there the courses (ABODA Victoria, 2018). So, in a sense, it wasn’t the fault of the Australian band movement that they kept to the status quo for so many years – there was no alternative.

Qualifications:

Regarding the points made about the musical knowledge of conductors at the time, there were some interesting stories about conductors who prided themselves and were very confident about their abilities as conductors. Once instance was in 1914 when the then conductor of the Wagga Town Band, Mr. W. G. Philpott took umbrage to malicious rumours that had been circulating about him – “Old Philpott and his mob” (and other rumours about drinking) – so he issued a challenge to Mr. A. Long, conductor of the Junee Municipal Band which was republished in various regional newspapers (“Bandmaster’s Challenge.,” 1914).

I, the undersigned, hereby challenge Mr. A. Long bandmaster, or prospective bandmaster of the Junee Municipal Band, to compete against me for a knowledge of the science of music, from the most elementary rudiments to the highest branches of theory, harmony, counterpoint, and fugue composition, and instrumentation; […] I also challenge Mr. Long to compete against me as a bandmaster for a knowledge of the acoustic properties of all brass band instruments and scientific tuning, band training and conducting.

(Philpott in “Bandmaster’s Challenge.,” 1914)

There was more to this challenge including getting the bands to face off against each other. It is interesting that the very facets of musical knowledge that Mr. Philpott is using as a challenge are the streams of knowledge that Mr. Ord Hume and others are saying that several Australian bandmasters lack. Perhaps they were right, and Mr. Philpott was an exception. Further to this little story, this was all there was in the papers about this. The challenge was issued but it appears there were no further developments.

The Longreach Town Band marching band in a procession to the Railway Station, leaving for Townsville to compete in the band contests at Easter, 1928. (Source: State Library of Queensland: 167364)

Bandmasters came to bands with a range of experiences and qualifications. So what were bands after, aside from the seemingly obligatory cornetist? Let us look to the Longreach Town Band where in 1928 they undertook a search for a new bandmaster. They presented a rationale for this decision which was at the head of a long article published in The Longreach Leader newspaper in June 1928.

At a meeting of the committee of the Longreach Town Band on Monday the terms under which the present Bandmaster (Mr. F. Affoo) was employed were fully discussed, and it was eventually decided that he could not be re-engaged under his terms, and applications are to be called through the Press for a new Bandmaster.

(“LONGREACH TOWN BAND.,” 1928)

The experience of the Longreach Town Band is actually a very useful case study as a month later, another article was published in The Longreach Leader newspaper which detailed some of the discussion of the committee and it detailed the qualifications and experience of all fifteen applicants. There were some interesting points of view from the committee.

Mr. Cullimore contended that the first point to consider was the musical ability of the man they wanted and then the finance unless they got a good man it was certain they would not get the public support.

Mr. J. Coates did not agree; he thought the first and vital point to consider was finance, with musical ability next. The Band was not in the fortunate position of the Longreach Football League who received big gates for their matches. The Band had to depend upon money from concerts.

Mr. Browne disagreed with Mr. Coates. For a little extra money that might be involved a good man would be far more satisfactory to the Band and the public; the public would support the band for a fist class man but not for a conductor that was no good.

(“New Bandmaster for Longreach.,” 1928)

From looking through the applications of the fifteen bandsmen who applied for the Bandmaster position at Longreach, we can see some patterns emerge.

- Twelve out the fifteen were already conductors of bands with two of them having the additional experience of having conducted an orchestra and a choir. The other three had no conducting experience with one of those three a Mr. Alf Cereso of Red Hill, Brisbane only stating that he had “wide experience in concert work.”

- Eight of the applicants were Cornet players, some of whom listed their competition successes, others who just listed that they had fulfilled the role of Solo or Soprano Cornetists with various bands. Five did not list which instrument they played. Unusually for an application to become a bandmaster, Mr. A. E. Gallagher from Wallsend, N.S.W. proudly noted that he had been the Solo Euphonium and Baritone of the Newcastle Steelworks Band on their tour to England – but he had no conducting experience.

- Another interesting pattern can be observed from these applications. Several of the bandsmen who applied listed that they had been part of many bands in the past, either as a player or conductor. We might call these bandsmen, ‘Journeyman Bandsmen’. In a measure of where these bandsmen had been, eleven had experiences in multiple bands. Out of those eleven, four had experiences with bands in other countries – two of them in New Zealand and two in England. And out of those eleven, most had experience from interstate bands with Victoria and New South Wales being most prominent. Some of the bands from interstate were impressive – Mr. V. Braddock (Warragul, Victoria) had played Cornet with the Malvern Tramways Band on their tour to New Zealand, Mr. F. A. Nicholls (Nundah) had once played professional cornet with the Geelong Harbour Trust Recreation Band Club, and it has been mentioned re Mr. A. E. Gallagher who had played Euphonium and Baritone with the Newcastle Steelworks Band. And some of these applicants claimed military band experience as well.

(This data was summarised from “New Bandmaster for Longreach.,” 1928)

The band had to make a choice, and this was detailed near the end of the article.

After considerable discussion it was decided that Arthur J. Rees’ application should be accepted (terms £2/10/ weekly, with position, or £5 a week until a position could be secured for him.)

Mr. Fred Wedd, Innisfail was second choice, and Mr. Geo. B. Shakespeare (Longreach) was third choice.

(“New Bandmaster for Longreach.,” 1928)

The application from Mr. Rees had been quite detailed.

Over 40 years of age, with more than 20 years experience as player and conductor of contesting bands at Home (England), and also several years experience as conductor of male choirs; in Australia six months: at present conductor of Parkes Band, which position he secured out of 17 applications; but was desirous of leaving because employment could not be found for him; started a band of learners at Parkes (19 strong), and about September or October next expected his two sons (17 and 19 respectively) from England, who were good solo cornetists at present playing for T. J. Rees, the well-known conductor of South Wales; these boys would be brought to Longreach if positions could be found for them later on; he was receiving £2/10/ – at Parkes.

(“New Bandmaster for Longreach.,” 1928)

Employment outside of the band was a contributing, and necessary factor in these times. A previous post about Australian bands during the Great Depression touched on the issues regarding bandsmen being employed in and around where bands were located (de Korte, 2020b).

There is much we can take from this section regarding the qualifications and experience of bandmasters, and the fact that bands wanted bandmasters who were skilled Cornet players. Clearly, some disagreed with this practice, and they had their reasons. While some Bandmasters were very experienced, it could be argued bandmasters on a whole needed some real training specific to their position. This will be detailed in the next section.

To conclude, bandmasters were revered by many. In October 1908, an impassioned letter was published in The Ballarat Star newspaper asking municipal authorities to do what they could so that Mr. Albert Wade, then conductor of the Ballarat City Band, might stay in Ballarat. The letter was countersigned by many of the leading musical figures in Ballarat led by Mr. Fred Sutton (Sutton et al., 1908).

The many plans:

This section will examine the crux of the issues outlined in the first two sections, that of actual training for bandmasters. Over the course of fifty years, many plans were put forward to provide training to bandmasters as it was perceived, and in some cases demonstrated, that bandmasters lacked proper training which was applicable to their positions. However, this was where band associations and conservatoriums could have been more proactive. The evidence shows that many plans were put forward to train bandmasters. The evidence also shows that none of these plans came to be. This is not to say that some of the training bandmasters were receiving through their experiences in bands was wholly bad as there were some legendary conductors coming through. But overall, it could have been much better.

It must be recognized that many Australian bandmasters did not have the support of their local towns to send them overseas for more musical training, Percy Jones being a prime example as the city of Geelong paid for him to go to Europe to study (“BANDMASTER PERCY JONES.,” 1907). An Australian system had to be found.

In the second section, an article on improving band music published in The Age newspaper was quoted with the author making some pertinent points. The author also suggested some solutions regarding training.

England has its Kneller Hall, where bandsmen are trained in all that appertains to their work; other countries have similar institutions. Why not Australia? Here, if following the English model, bandsmen – training as professionals – could be taught music on the best academic lines, and these would be the men who would act the standard of band cultures throughout the country. No very large amount would be required, and if the band associations move in the matter there seems no reason why a workable scheme should not take shape.

(“IMPROVEMENT OF BAND MUSIC.,” 1912)

There are a few things to unpack out of this paragraph that provide some context. One is the issue of tuition for bandmasters. Fair enough, they probably should have more knowledge to do their jobs and a school for bandmasters would probably be useful. But setting up an institution like the famed Kneller Hall in Australia purely for the training of largely amateur bandmasters was probably a bit too much. It was not the first time Kneller Hall would be mentioned in connection with these plans.

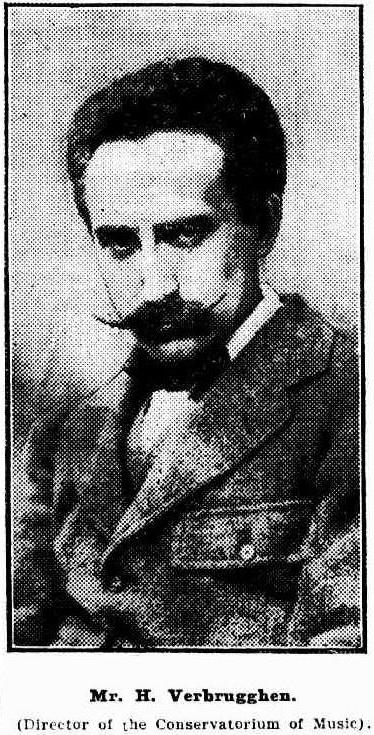

Mr. Henri Verbrugghen was a superb Belgian violinist and down-to-earth musician who was chosen to become the foundation head of the new N.S.W. Conservatorium of Music in 1915 (Carmody, 2006). By all accounts, he was a truly great teacher and administrator, and he recognized that musical training should be open to all. He also knew that there were many genres of music that people participated in, and he wanted to offer courses at the Conservatorium that would cater for all kinds of musicians, including those who were part of the brass band movement.

To this end special provision is to be made for the formation of a school of brass and military band instrumentation in the Conservatorium. Classes for the teaching of all a well-equipped bandmaster ought to know will be formed, and those who direct or intend to direct bands will be given every opportunity for perfecting themselves in the art of conducting. […] The scheme will take a little time to perfect, but the director is confident that if sufficient brass and reed students present themselves there will be no difficulty in finding the instructors among our local professional ranks.

(“CROTCHETS AND QUAVERS,” 1915)

This was very forward thinking by Mr. Verbrugghen, especially when considering the local conditions at the time. What is not apparent is whether these classes were fully introduced – it would have been transformative if they had gone ahead. In saying so, he respected the band movement. He adjudicated at the South Street Eisteddfod in 1921 where he was very impressed with the playing of the brass bands (“HENRI VERBRUGGHEN ON BRASS BANDS.,” 1921). So much so, that after South Street had concluded, he invited the Malvern Tramways Band to perform with his own orchestra, a fine compliment paid to this band (“MUSIC.,” 1921).

(Source: Jeremy de Korte personal collection)

In the 1930s, a flurry of articles was published in Tasmania and Queensland newspapers advocating for institutions to be set up specifically for the training of bandsmen and band conductors. Again, had these plans been carried beyond the talking stage then they would have made a difference. Unfortunately, none of them did. We see that in 1933 that comments were made by music critic Mr. F. Bonavia where he thought that conducting classes at music festivals might be a good idea, however, he acknowledged that a few weeks of teaching would not be long enough (“Amateur Conductors.,” 1933).

1934 saw the official launch of the Australian Band Council. This was covered in a previous post, but one item that was mentioned was the setting up of a “school of band music, on lines similar to the Knellar Hall in England.” (de Korte, 2019; “HALL OF BAND MUSIC,” 1934). A fine idea, but it was an idea that was subsequently dropped due to expense (“BAND CHAMPIONSHIPS,” 1934).

The Mercury newspaper published an interesting article in 1934 where, again, the need for training conductors was highlighted, especially in the band movement. This was the year that Capt. Adkins was taking the A.B.C. Military Band on tour around the country, and he was interviewed by various newspaper around the country. The Mercury quoted and summarised Mr. Thorold Waters who had penned an article in the Australian Musical News.

Mr. Waters adds that as far as anyone seems to be aware there is not in the whole Commonwealth any place or man to whom the student might turn for lesson in conducting. He stresses the urgent need to founding a school for conductors – not necessarily an institution as complete as Kneller Hall – but one where the bad fashions of conducting rife in Australia could be altered at small cost.

(“MUSIC AND MUSICIANS,” 1934)

This is probably the most useful statement on setting up a conducting school as it clearly says that a school is necessary, but it did not have to be like Kneller Hall of which so many writers and other administrators thought was needed for Australian bandmasters.

In a final word from these fifty years of plans and ideas, Mr. D. T. Beston, Secretary of the Australian Bands’ Council, suggested that “Tasmania should open up new fields for training bandsmen” – whatever this means (“TRAINING FOR BANDSMEN,” 1949).

Fifty years of plans with nothing much to show for it. Thankfully, in recent times, the training of conductors has become fully ingrained with the Conservatoriums and we have professional associations like ABODA to provide specific courses (ABODA Victoria, 2018).

Conclusion:

There is no doubting that these three intertwined issues surrounding the training and qualifications of Australian bandmasters were complex, opinionated, fractured and not very forthcoming. And history has not been kind. Why would it be? The Australian band movement faced an amount of criticism by those who did not really understand the Australian context or needs of Australian bands and bandmasters. It was not the fault of the Australian band movement that some conditions, like the employment of Cornetist-Bandmasters was kept up for so many years in the face of no other option. These ‘critics’ ignored the significant achievements of Australian bands at home and abroad.

Certainly, if the band associations and conservatoriums had worked to provide more training for bandmasters, a difference could have been made. The musical leaders of the time probably felt let down. But they persevered, and many of our bands survived. The Australian band conductors of the past, present and future should be congratulated for their work.

References:

ABODA Victoria. (2018). About. ABODA Victoria. Retrieved 11 January 2022 from https://abodavic.org.au/about/

Advertising. (1911, 21 April). Areas’ Express (Booyoolee, SA : 1877 – 1948), 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article219438866

Advertising. (1914, 07 November). Daily Standard (Brisbane, Qld. : 1912 – 1936), 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article178849383

Advertising. (1926, 06 August). Cowra Free Press (NSW : 1911 – 1937), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article262027016

Almond, H. C. (1916, 11 March). Advertising. St George Call (Kogarah, NSW : 1904 – 1957), 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article162766364

Amateur Conductors. (1933, 08 February). Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954), 11. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article24710870

AUSTRALIAN BANDS : Lack Good Conductors : SAYS THE KING’S TRUMPETER. (1908, 13 November). Australian Star (Sydney, NSW : 1887 – 1909), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article229091651

BAND CHAMPIONSHIPS. (1934, 23 April). Courier-Mail (Brisbane, Qld. : 1933 – 1954), 16. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1192269

BAND CONDUCTORS : Criticism Justified. (1925, 13 June). News (Adelaide, SA : 1923 – 1954), 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article129736006

BANDMASTER PERCY JONES. (1907, 30 November). Geelong Advertiser (Vic. : 1859 – 1929), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article149219732

Bandmaster’s Challenge. (1914, 20 June). Armidale Chronicle (NSW : 1894 – 1929), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article187607478

Carmody, J. (2006). Verbrugghen, Henri Adrien Marie (1873-1934). In Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 29 December 2021, from https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/verbrugghen-henri-adrien-marie-8913

CROTCHETS AND QUAVERS : CONSERVATORIUM PROGRESS : MILITARY BAND SCHOOL : THE MELBOURNE RECITAL. (1915, 17 October). Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 – 1954), 22. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article221915763

de Korte, J. D. (2019, 05 June). Finding National consensus: how State band associations started working with each other. Band Blasts from the Past : Anecdotes, Stories and Personalities. https://bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2019/06/05/finding-national-consensus-how-state-band-associations-started-working-with-each-other/

de Korte, J. D. (2020a, 21 May). Choosing music and grading bands: The unenviable tasks of band associations and their music advisory boards. Band Blasts from the Past : Anecdotes, Stories and Personalities. https://bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2020/05/21/choosing-music-and-grading-bands-the-unenviable-tasks-of-band-associations-and-their-music-advisory-boards/

de Korte, J. D. (2020b, 18 October). Testing times: the resilience of Australian bands during the Great Depression. Band Blasts from the Past : Anecdotes, Stories and Personalities. https://bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2020/10/18/testing-times-the-resilience-of-australian-bands-during-the-great-depression/

de Korte, J. D. (2021, 16 February). Influences from Britain: James Ord Hume and “The Besses Effect”. Band Blasts from the Past : Anecdotes, Stories and Personalities. https://bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2021/02/16/influences-from-britain-james-ord-hume-and-the-besses-effect/

Doak, H. (1908, 24 July). Advertising. Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 – 1930), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article238170790

Dulcet. (1925, 15 June). Band Conductors. News (Adelaide, SA : 1923 – 1954), 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article129734100

Elwin, G. B. (1913). Wanted [Advertisement]. The State Band News, 4(6), 21.

AN ENTHUSIASTIC MUSICIAN : Mr. W. H. Foote Interviewed. (1921, 16 March). Register (Adelaide, SA : 1901 – 1929), 7. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article63043619

A GREAT BANDMASTER : LIETENANT J. ORD HUME IN ADELAIDE : AUSTRALIAN BANDSMEN PRAISED. (1924, 30 October). Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1889 – 1931), 10. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article73434557

Green, W. C. (1911, 23 March). Advertising. Examiner (Launceston, Tas. : 1900 – 1954), 7. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article50467046

HALL OF BAND MUSIC : Australian Proposal. (1934, 05 April). Central Queensland Herald (Rockhampton, Qld. : 1930 – 1956), 8. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article70310251

Harris, J. (1910, 08 November). Advertising. Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 – 1930), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article238666818

HENRI VERBRUGGHEN ON BRASS BANDS. (1921, 06 December). Toowoomba Chronicle (Qld. : 1917 – 1922), 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article253315624

IMPROVEMENT OF BAND MUSIC. (1912, 02 March). Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954), 24. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197401629

Levy, W. (1925, 16 June). Band Conductors. News (Adelaide, SA : 1923 – 1954), 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article129729171

LISTEN TO THE BAND! : Appeal by President : MORE PUBLIC SUPPORT NEEDED. (1925, 09 April). News (Adelaide, SA : 1923 – 1954), 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article129718612

LONGREACH TOWN BAND : FULL DISCUSSION ON BANDMASTER’S POSITION : APPLICATIONS TO BE CALLED FOR BANDMASTER. (1928, 15 June). Longreach Leader (Qld. : 1923 – 1954), 12. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article37342371

Madge, C. J. (1925, 15 June). Band Conductors. News (Adelaide, SA : 1923 – 1954), 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article129734100

Michell, A. B. (1925, 29 June). Band Conductors. News (Adelaide, SA : 1923 – 1954), 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article129735730

MR. J. ORD HUME : AN INTERESTING INTERVIEW : WHAT AUSTRALIAN BANDS LACK. (1903, 25 February). Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article208462723

Mr. Verbrugghen’s Return. (1918, 03 April). Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 – 1919), 47. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article263622163

MUSIC AND MUSICIANS : Mr. F. J. NOTT : Bands and Band Music. (1932, 23 November). Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article24688707

MUSIC AND MUSICIANS : SCHOOL FOR CONDUCTORS : Urgent Need. (1934, 14 March). Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article24918478

Musical band procession in Longreach, 1928. (1928). [photographic print : black & white]. [167364]. Brisbane John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Queensland. https://hdl.handle.net/10462/deriv/132618

New Bandmaster. (1919, 18 January). Port Macquarie News and Hastings River Advocate (NSW : 1882 – 1950), 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article105147517

New Bandmaster for Longreach : CONDUCTOR OF PARKES BAND APPOINTED. (1928, 27 July). Longreach Leader (Qld. : 1923 – 1954), 21. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article37340861

NEW DIRECTOR FOR TRAMWAYS BAND : Mr. W. H. FOOTE APPOINTED. (1922, 18 February). Daily Herald (Adelaide, SA : 1910 – 1924), 7. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article106648236

The Newly Formed Victorian Bandmasters’ Association. (1931). In S6.3.1 – Album Projects (Photocopies) (Photocopies of printed photographs ed., Vol. Album 3). Victoria: Victorian Bands’ League Archive.

Ord Hume, J. (1909, 04 November). Training a Bandsman : THE AFTER EFFECTS OF POOR TUITION : (By Mr. J. Ord Hume, in “The British Bandsman.”). Cairns Post (Qld. : 1909 – 1954), 7. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article39381330

PERSONAL. (1924, 04 October). Register (Adelaide, SA : 1901 – 1929), 8. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article57882534

Rose, G. (n.d.). Conservatorium of Music, Sydney, N.S.W. [Postcard]. [The Rose Series P. 5055]. Rose Post Cards, Armadale, Victoria.

SAVE THE BAND : VIEW OF MR. FOOTE : Corporation Levy Favored. (1925, 01 April). News (Adelaide, SA : 1923 – 1954), 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article129711540

Smith, A. (1907, 16 September). Advertising. Bunbury Herald (WA : 1892 – 1919), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article87152593

Sutton, F., Gude, W., Opie, T., West, H., Mooney, J. T., Eyres, C., Bailey, J. C., Boustead, W. M., Hautrie West, W., & Herbert, G. (1908, 27 October). CORRESPONDENCE : THE CITY BANDMASTER : To The Editor of ‘The Star’. Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924), 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article218563934

Thirst, T. (2006). James Ord Hume 1864-1932 : a friend to all bandsmen : an account of his life and music. Timothy Thirst.

TRAINING FOR BANDSMEN. (1949, 03 November). Advocate (Burnie, Tas. : 1890 – 1954), 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91771050

UNLEY MUNICIPAL BAND : Progressive and Ambitious : CREDIT TO CITY. (1925, 23 January). News (Adelaide, SA : 1923 – 1954), 10. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article129828551

Wales, N. S. (1918, 28 November). Advertising. Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 12. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15813101