Introduction:

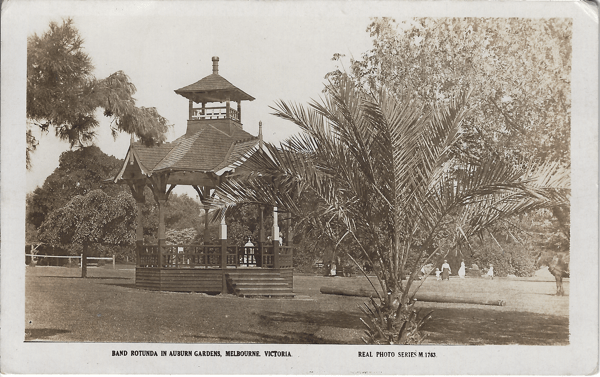

They stand in parks and gardens throughout Australia as monuments to public entertainment before the days of broadcasting music through the wireless. A source of civic pride, they are of a distinct purpose, yet cover a very wide variety of design and architecture. They were built as memorials to musicians, royalty and service personnel, for bands and bandmasters, and also for the towns. If there is one structure that provides a perfect linkage between a locality, people and a band it would have to be the band rotunda.

Nowadays, as it was when they were first built, we take pride in their aesthetic appeal. They may not be used as performance platforms anymore as the bands they once served are no longer in operation. Nevertheless, they still stand, often painted in heritage colours and with plaques on the sides we can learn of the story a rotunda. A source of fascination for many.

The band rotundas have been a focus for academic and local studies over time as they can help tell parts of the history of architecture and music in this country. This post is not seeking to replicate the valuable work that has already been completed in documenting band rotundas. However, there are numerous little stories that can be told, and this post will seek to complement previous work, as well as display numerous photographs.

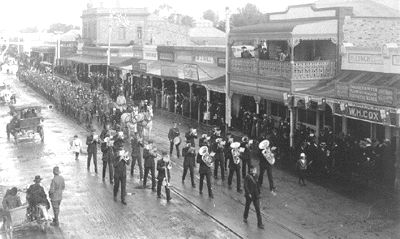

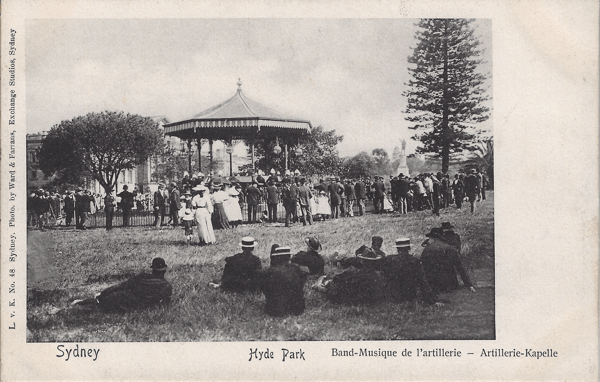

At the head of this post is a postcard showing an Artillery Band playing at the Hyde Park band rotunda with people watching around the sides, obviously appreciating the playing. This idyllic scene could have been repeated anywhere when bands played at the local rotunda. Suffice to say, with growing preservation and appreciation of these structures, as well as the building of new rotundas, music is being heard once again; the old is back in fashion.

History not forgotten:

Much has been written and studied about band rotundas in Australia, and all of it is worthwhile information. The rotundas are the subject of many photos and postcards, and, as mentioned, they have also informed some of the history of architecture. There are too many rotundas in Australia for this post and other writing to do them all justice, which is unfortunate. Regarding academic study, Tracy Videon documented the history of rotundas in Victoria for her Master of Arts thesis (Videon, 1996). This thesis has been cited in other heritage studies by local councils, for example, the Shire of Mount Alexander (Jacobs et al., 2004/2012).

Interest in the rotundas has also been displayed periodically on social media with the advantage of having other like-minded people post and link their own stories. In 2017, Michael Mathers posted on Facebook about the rotunda in Kew that he used to play at with the Kew Band and invited responses from other people (Mathers, 2017). I have also posted on Facebook regarding band rotundas through displaying parts of my historical collection of postcards – one post relating to the postcard of the Artillery Band at Hyde Park, Sydney (de Korte, 2020c). Through communication with band historians on Facebook, other resources have come to light such as the book, ‘Band Rotundas South Australia’ written by Brenton Brockhouse, historian of the Campbelltown City Band in Adelaide where he documented all the band rotundas in South Australia (Brockhouse, 2016).

Perhaps the most important resource that has been created about band rotundas in recent years is the book, ‘Pavilions in Parks : Bandstands and Rotundas Around Australia’ by Allison Rose with photographs by Belinda Brown. This book is very useful as it details the architecture and design of each rotunda and highlights the history and civic pride (Rose, 2017). It is understandable that Rose could not cover every rotunda in Australia. However, she does tell us how she made choices by saying that each rotunda in her book was “chosen for architectural, historical or social significance” (Rose, 2017, p. 5). Importantly she also states that the word “Bandstand” is used to describe its “major function” but is also known as a “rotunda, pavilion or, in earlier times, kiosk or orchestra.” (Rose, 2017, p. 5).

In terms of the history of this building type, Rose informs us that its history is long and examples can be found in classical Greece, 7th Century Persia and 16th & 17th Century India (Rose, 2017). The designs of these early structures were replicated in England in the 1800s and from this came the development of bandstands which were used for musical performances (Rose, 2017). And as Rose (2017) tells us, the location and function of a bandstand was important.

A bandstand in the park had a useful social purpose. It brought music to many people who would have no other opportunity to hear it, it was a way to meet old friends and for the young to find new friends

(p. 7)

In Australia, the custom of the time was to follow the traditions and architecture of the British homeland and to this end, they proliferated across the country. As in England, the purpose of these rotundas was the same and they also gave new opportunities for people to hear music.

The concert in the town bandstand was often the only opportunity for people to hear live music as well as to socialise.

(Rose, 2017, p. 12)

Regarding building materials, many rotundas were built using cast iron columns and lacework which later evolved into timber features (Rose, 2017). They were mainly built up until the First World War and in between wars, the building of bandstands “almost came to a halt” (Rose, 2017, p. 16).

After the Second World War, the building of outdoor performance spaces was dominated by concrete “sound shells” of which some were “well-designed, but others were extremely ugly” (Rose, 2017, p. 16). Thankfully, Rose details in her history that the appreciation of rotundas was noted in the 1980s and many rotundas were saved from demolition, and in many localities, they have found new uses for them.

Today, there is interest in bandstands for their practical uses as well as their decorative function and towns and suburbs are building new bandstands. Some are in Federation style, others provide a more contemporary home for today’s musical events…

(Rose, 2017, p. 16)

We are lucky that so many rotundas have been preserved for the current generations to enjoy.

Bands and Rotundas:

There is a synonymous relationship between bands, rotundas and local communities. A locality expresses pride through a band, but the band needs a place to perform on a regular basis. A rotunda is then built for the benefit of the town band and the community and the rotunda becomes focal point for the community. There is more to this of course and with each rotunda that has been built and survives, “each has a story to tell.” (Rose, 2017, p. 5).

A letter written by a person with a pseudonym “A Lover of Music” was published in the Mount Alexander Mail newspaper on the 23rd of January 1893 to berate the local council over the lack of a permanent rotunda in Castlemaine.

Sir, – I have often wondered that Castlemaine has been so long without a suitable place for the band to perform in. I can’t understand why the Council have not sufficient enterprise to erect a “rotunda” in the Botanical Gardens. Every concert in the Gardens necessitates the erection of a temporary platform. It has struck me that as our worthy Mayor is a Welshman – and, of course, fond of music – it would be a graceful act on his part to have erected a rotunda worthy of our town and of the band, and to present it to the Council. […] I trust that the Mayor and Councillors will see that very soon our splendid band will have a proper place to perform in. My main object in mentioning this matter is to show my appreciation of the band.

(A Lover of Music, 1893)

It took another five years, but finally in 1898 a band rotunda was built in the Castlemaine Botanical Gardens where it was opened by the Mayor with a concert presented by the Thompson’s Foundry Band (“CASTLEMAINE.,” 1898). A rotunda still exists in the gardens to this day.

In 1909, a rotunda that was described as “commodious and ornate” was opened in the town of Nhill in Western Victoria by the Mayor and some local parliamentarians (“NHILL.,” 1909). The Nhill Town Band was said to be in “high feather” about the new rotunda and during the concert, some bandsmen also demonstrated how civic minded they were by leaving the bandstand to help with a nearby house fire (“NHILL.,” 1909). The Nhill band rotunda is very much a civic landmark and was refurbished in 2018 by the local council (Hindmarsh Shire Council, 2018).

Some rotundas were not built by the local councils or bands and it is interesting to find an example of a rotunda that was built by a private company for the use of the local band and the town. The Portland Brass Band from New South Wales was the beneficiary of this investment when the local cement company, which supported the band as well, built a band rotunda in Portland.

The band rotunda, recently erected by the cement company for the use of the band, was officially opened on Saturday night by Dr. A. Scheidel, the managing director. Mr. J. Saville, the works manager, was also present. The bandsmen were in uniform, and when all were assembled, the doctor switched on the light and addressed the bandsmen. He said that the rotunda had been erected by the company as an appreciation of their efforts. He hoped that they would see that no injury would be done to the building, and looked to the townspeople generally to assist with that object.

(“BAND ROTUNDA FOR PORTLAND.,” 1910)

This article, which was published in the Lithgow Mercury newspaper, also provided an excellent description of this newly built structure.

The bandstand is a very neat structure, octagonal in shape. It is nicely painted in two shades of green, relieved with white. It is lit with eleven incandescent electric lights of sixteen candle power each. Eight of these are arranged round the sides, while a group of three is suspended from the centre of the ceiling. When lit up, it presented a very brilliant appearance.

(“BAND ROTUNDA FOR PORTLAND.,” 1910)

A photograph of the original rotunda can be found on the Facebook page of the Lithgow & District Family History Society Inc. (2015). In 2017 a new rotunda was opened in Portland where the local parliamentarian is quoted in an article published by the Lithgow Mercury newspaper.

The rotunda is a reflection of the past, of Portland’s history with the original structure providing a backdrop for many events and occasions when the community came together to enjoy music by the local band.

I have no doubt the new rotunda will provide a great place for the local band to again deliver some fantastic events to the residents of Portland. It will enhance the landscape of the surrounding park, provide a comfortable place to sit, relax and enjoy music from a band or perhaps even a string quartet.

(Toole in “Portland’s bandstand rotunda is officially opened for all.“, 2017)

These sentiments sound very familiar to those of times past.

Commemorative rotundas:

Often, rotundas were built to serve a commemorative function in addition to their stated purpose. We can see an example above in this rotunda from Wollongong which was built to commemorate the landing of “Bass and Flinders in 1796” (“MEMORIAL TO NAVIGATORS.,” 1924). This of course is a commemoration to a very old event; however other rotundas were built to commemorate much more recent events.

In 1917, an article published in the Pinnaroo and Border Times agitated for a rotunda to be built in town which would benefit the town band (“Band Rotunda Wanted.,” 1917). The writer of this article is very eloquent in his words, and ties in town support for the Pinaroo Brass Band as a key element in wanting a rotunda for them to perform in.

The town owes a duty to these unselfish bands of musicians who give their services gratis and pay fees for the privilege of doing so. No complaint emanates from the members on this score, but that they are entitled to practical help – which may be given by a strong roll of honorary membership – cannot be refuted. An opportunity now presents itself of showing this appreciation by inaugurating a movement for a rotunda which many country towns possess. Not only would a rotunda facilitate and render more comfortable outdoor playing, but the music could be heard to a greater advantage, and the building, if artistically designed, would be a welcome ornament to the Show ground or any other favourable site.

(“Band Rotunda Wanted.,” 1917)

The Pinnaroo Band Rotunda was eventually built in 1922 to commemorate people of the district that saw service during World War One (Virtual War Memorial Australia, n.d.). In 1935 it was renovated and extensive repainting was undertaken, as well as other sundry repairs in the vicinity (“BAND ROTUNDA RENOVATED,” 1935). The band rotunda still stands to this day.

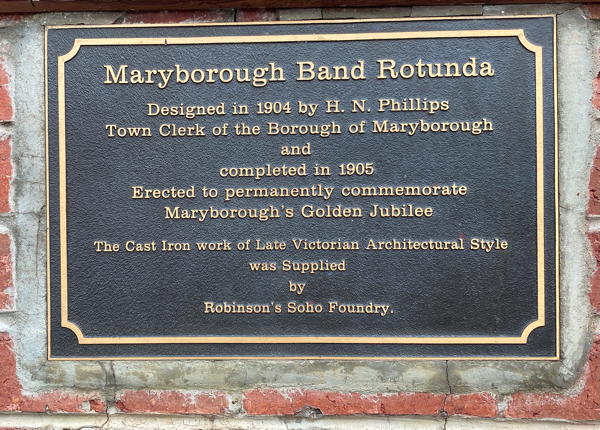

The band rotunda at Maryborough in Victoria is another interesting example. This structure was built in 1904 and as the plaque below reads, this was built to commemorate Maryborough’s Golden Jubilee. As a band rotunda, this is one of the more ornate examples that exist.

In the township of Merbien, a little way west of Mildura in the far North-West of Victoria, a band rotunda was built to commemorate King George V who died in 1936. The postcard below shows us what it was like in its early days, and the events of when it was opened in 1937 were documented in an article published by the Argus newspaper.

…To-day the third day of the jubilee celebrations was a quiet day for Mildura, but Merbien was the centre of intense activity. A dense crowd gathered in Kenny Park for the unveiling of the King George V. Memorial by the Postmaster-General Senator McLachlan.

[…]

Senator McLachlan said it was a tribute to the people of Merbien that they had erected such a fine memorial to a King whose influence was for righteousness and peace.

(“MEMORIAL TO KING GEORGE,” 1937)

One of the more famous band rotundas that was built to commemorate an event is the Titanic Memorial Band rotunda in Ballarat. Allison Rose has documented this rotunda in her book, and this rotunda is the focus of a commemorative event each year. The opening of this rotunda was noted all over Australia, especially because the costs of erecting this structure was due to bandsmen from all over the country contributing a subscription (“Local and General.,” 1915). The Evening Echo newspaper from Ballarat described the opening of the memorial in an article published in October 1915.

This memorial has been built to commemorate the heroic bandsmen of the White Star liner Titanic (45,000 tons), which met her doom by striking an iceberg in the Atlantic two years ago.

It is on record that the ships band mustered on deck and played “Nearer My God to Thee,” and then went down with the ship, all of them being lost. When the news of their sublime courage reached Australia the idea immediately occurred to some one that the bandsmen of Australia should place on permanent record their appreciation and it was suggested that I should take the form of a memorial bandstand.

(“TITANIC MEMORIAL.,” 1915)

It is no accident that this memorial bandstand was erected in Ballarat as it was, by this time, regarded as one of the band centres of Australia thanks to the South Street events (Rose, 2017). Indeed, when this memorial was opened in October 1915, the South Street events were well-underway and there was no shortage of bands in town to combine in a massed band conducted by Albert Wade (“TITANIC MEMORIAL.,” 1915). Interestingly, as Rose (2017) tells us,

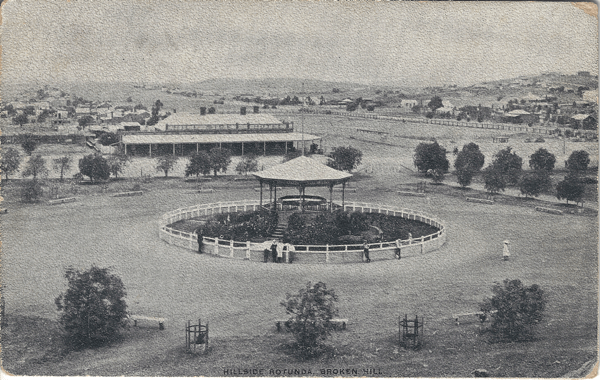

It is unique among the bandstands of Australia in being a memorial to the Titanic bandsmen. The citizens of Broken Hill attempted to build such a bandstand, but they could not raise sufficient funds by public subscription. With the money raised they had to settle for a broken column memorial that now stands in Sturt Park in Broken Hill.

(p. 80)

Proposals, building and public opinion:

In the early years when building band rotundas was a fashionable thing to do, many proposals were submitted to local councils, and some were for alterations to existing precincts. Civic pride accounted for the fact that many proposals were accepted – although there were some who objected. Finding an objectionable letter to any rotunda was rare. In 1907 a Mr Angove of Albany, Western Australia expressed surprise that the local council was going ahead with the building of a rotunda in Lawley Park (Angove, 1907). His letter, published in the Albany Advertiser newspaper, mainly raised the question of expense, of why the council was diverting funds to a rotunda instead of other “urgent works” (Angove, 1907). An understandable attitude at the time.

Proposals for band rotundas, as has been seen earlier in this post, mainly appealed to the goodwill of councils and the public, and drew in the needs of the local bands as well. For example, we can see in articles regarding proposals in Dandenong, Victoria, and Wallaroo, South Australia that detail how this kind of appeal was expressed (“A Band Rotunda Proposed.,” 1917; “WALLAROO ROTUNDA.,” 1925).

Input from bandsmen was also noted in the early newspapers, as they had more of a vested interest. “A Bandsman” from Scottsdale, Tasmania, wrote a letter to the North-Eastern Advertiser newspaper in November 1919 to complain about the proposed site of the new rotunda – (in summary) it was going to be too close to other buildings and out of sight – why not place it in a park? (A Bandsman, 1919). Likewise, “Carbolic” wrote to his local newspaper to congratulate the Glenelg Town Band on their recent performance, but advocated for the moving of the band rotunda to a more suitable location because of acoustics – there were nearby walls that affected the sound projection (Carbolic, 1918).

Maintenance was another issue (and an ongoing issue). While some were proactive about maintaining rotundas, it seems that some were not so proactive. In Broken Hill, a Mr H. R. Boyce wrote to the Barrier Miner newspaper to complain about creepers that were growing over the rotunda in the Central reserve (Boyce, 1923). The rotunda in Healesville faced a different maintenance issue in 1941 when lightning struck the rotunda which shattered a flagpole (“BAND ROTUNDA STRUCK BY LIGHTNING,” 1941). And in 1950 we find that the Brisbane City Council was unable to maintain rotundas to a satisfactory standard due to a lack of materials and labour (“CAN’T REPAIR BANDSTANDS,” 1950).

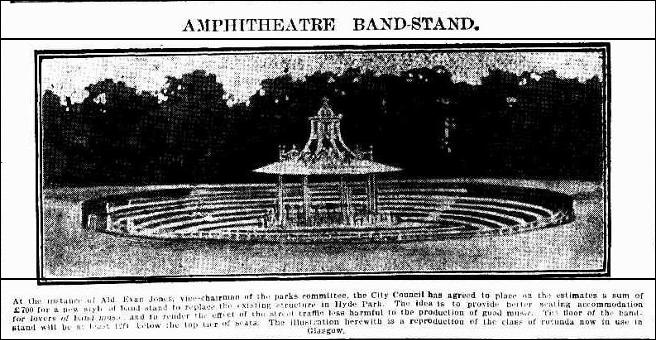

To finish this section, there were two pictures from newspaper articles that caught my attention. The first is a picture published in the Daily Telegraph newspaper in 1910 that shows a proposal to surround the band rotunda in Hyde Park with an amphitheatre.

This second picture shows the laying of the foundation stone for a new rotunda in Mount Gambier, no doubt a special occasion.

Conclusion:

These are special buildings. They are unique buildings. And they provide life for so many bands, people and localities. It is a shame that so many rotundas have been removed, but equally, it is worthwhile to see how many remain and are preserved as icons to a community. Each rotunda has a story to tell and the stories are interlinked with towns, suburbs and bands across Australia.

References:

A Bandsman. (1919, 11 November). Band Rotunda : (To the Editor.). North-Eastern Advertiser (Scottsdale, Tas. : 1909 – 1954), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article151262612

A Lover of Music. (1893, 23 January). CORRESPONDENCE : A BAND ROTUNDA. Mount Alexander Mail (Vic. : 1854 – 1917), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article198699429

AMPHITHEATRE BAND-STAND. (1910, 26 November). Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 – 1930), 15. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article238664637

Angove, W. H. (1907, 02 November). Lawley Park Rotunda : [To the Editor.]. Albany Advertiser (WA : 1897 – 1954), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article69959867

BAND ROTUNDA FOR PORTLAND. (1910, 24 August). Lithgow Mercury (NSW : 1898 – 1954), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article218492203

A Band Rotunda Proposed. (1917, 18 October). South Bourke and Mornington Journal (Richmond, Vic. : 1877 – 1920; 1926 – 1927), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66192904

BAND ROTUNDA RENOVATED. (1935, 17 May). Pinnaroo and Border Times (SA : 1911 – 1954), 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article189641733

BAND ROTUNDA STRUCK BY LIGHTNING. (1941, 16 January). Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article8171730

Band Rotunda Wanted. (1917, 10 August). Pinnaroo and Border Times (SA : 1911 – 1954), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article188360174

Band Rotunda, Castlemaine Gardens. (n.d.). [Postcard]. [Josef Lebovic Gallery collection no. 1]. Ward, Lock and Co Ltd, London and Melbourne. National Museum of Australia http://collectionsearch.nma.gov.au/object/140044

BANDSTAND BUILDING UNDER WAY AT VANSITTART PARK. (1933, 26 October). Border Watch (Mount Gambier, SA : 1861 – 1954), 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article77944349

Boyce, H. R. (1923, 31 October). THE ROTUNDA FOLIAGE : To the Editor. Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, NSW : 1888 – 1954), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article45624435

Brockhouse, B. (2016). Band Rotundas South Australia. Albumworks. https://my.album.works/2AhNhAf

Brokenshire, J. (n.d.). Hillside Rotunda, Broken Hill [Postcard]. Joseph Brokenshire, Broken Hill, N.S.W.

Bulmer, H. D. (n.d.). Main Street Gardens and Band Rotunda, Bairnsdale [Postcard]. Bulmer’s, Bairnsdale, Victoria.

CAN’T REPAIR BANDSTANDS. (1950, 30 August). Courier-Mail (Brisbane, Qld. : 1933 – 1954), 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article49731125

Carbolic. (1918, 22 August). BAND AND BANDSTANDS : To the Editor. Glenelg Guardian (SA : 1914 – 1936), 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article214715457

CASTLEMAINE. (1898, 23 November). Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article9861653

de Korte, J. D. (2019a). Ballarat Central, Vic. : Titanic Memorial Bandstand – Memorial Stone [Photograph]. Jeremy de Korte, Malvern, Victoria.

de Korte, J. D. (2019b). Ballarat Central, Vic. : Titanic Memorial Bandstand [Photograph]. Jeremy de Korte, Malvern, Victoria.

de Korte, J. D. (2020a). Maryborough, Vic. : Princes Park : Band Rotunda [Photograph]. [IMG_5902]. Jeremy de Korte, Redan, Victoria.

de Korte, J. D. (2020b). Maryborough, Vic. : Princes Park : Band Rotunda – Plaque [Photograph]. [IMG_5903]. Jeremy de Korte, Redan, Victoria.

de Korte, J. D. (2020c, 12 August). These are the latest additions to the historical band postcard collection that I’ve been putting together. The first one is of a Military Band playing at the bandstand in Hyde Park, Sydney. Unfortunately, the band and year are unknown but the scene it creates could probably be replicated around any bandstand… [Post]. Facebook. Retrieved 29 November 2020 from https://www.facebook.com/groups/145016798904992/permalink/4120772517996047

Hindmarsh Shire Council. (2018). Goldsworthy Park, Nhill [Newsletter]. Monthly Newsletter (October), 3. https://www.hindmarsh.vic.gov.au/content/images/what’s%20on/Monthly%20Newsletter/2018/Monthly%20Newsletter-Hindmarsh%20Shire%20Council-%20October%202018.pdf

Jacobs, W., Taylor, P., Ballinger, R., Johnson, V., & Rowe, D. (2004/2012). Shire of Mount Alexander : Heritage Study of the Shire of Newstead : STAGE 2 : Section 3 : Heritage Citations: Volume 3 : Newstead [Report](6205). (Heritage Studies, Issue. Shire of Mount Alexander. https://www.mountalexander.vic.gov.au/Page/Download.aspx?c=6205

Local and General : Titanic Memorial. (1915, 13 September). Bathurst Times (NSW : 1909 – 1925), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article111229166

Mathers, M. (2017, 12 August). Most of us have (or had) a local Band Rotunda. Do you have a photo of it (the older the better) ? This is the one in Kew, Melbourne (a band with which I used to be a player). Upload yours [Post]. Facebook. Retrieved 29 November 2020 from https://www.facebook.com/groups/472757142742103/permalink/1844534445564359

MEMORIAL TO KING GEORGE : Merbein Ceremony. (1937, 11 August). Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), 7. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article11116265

MEMORIAL TO NAVIGATORS. (1924, 17 May). Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 13. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28072947

NHILL : NEW BAND ROTUNDA. (1909, 05 October). Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924), 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article218793589

Portland’s bandstand rotunda is officially opened for all. (2017, 11 December). Lithgow Mercury . https://www.lithgowmercury.com.au/story/5111856/portlands-bandstand-rotunda-is-officially-opened-for-all/

Queenscliffe Hotel Kingscote. (1900). [Photograph]. [B+30375]. State Library of South Australia, Kingscote Collection. https://collections.slsa.sa.gov.au/resource/B+30375

Rose, A. (2017). Pavilions in parks : bandstands and rotundas around Australia . Halstead Press.

Tellefson. (1937). Band Rotunda Merbein [Postcard]. [Tellefson Series 4]. Tellefson.

TITANIC MEMORIAL. (1915, 22 October). Evening Echo (Ballarat, Vic. : 1914 – 1918), 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article241689331

Valentine & Sons Publishing Co. Ltd. (1924). Band Rotunda in Auburn Gardens, Melbourne, Victoria [Postcard]. [Real Photo Series M.1763]. Valentine & Sons Publishing Co. Ltd., Melbourne, Sydney & Brisbane.

Videon, T. (1996). “And the band played on …” band rotundas of Victoria (Publication Number 9924382201751) [MArts, Monash University, Faculty of Arts, Department of History]. Clayton, Victoria. https://monash.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/MON:au_everything:catau21172148940001751

Virtual War Memorial Australia. (n.d.). Pinaroo Sodiers Memorial Band Rotunda . Virtual War Memorial Australia. Retrieved 30 November 2020 from https://vwma.org.au/explore/memorials/684

WALLAROO ROTUNDA : Proposition by Town Band. (1925, 09 September). Kadina and Wallaroo Times (SA : 1888 – 1954), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article124763086

Ward & Farrans. (n.d.). Sydney – Hyde Park (Band-Musique de l’artillerie) (Artillerie-Kapelle) [Postcard]. [L. v. K. No. 48]. Exchange Studios, Sydney, N.S.W.