Introduction:

His duties as Librarian (self-imposed) were to clean up the room after practices and to arrange the various sets of music so as to have any particular set “right under his thumb,” if required, at a moment’s notice; which was itself no sinecure. No practice or public performance was complete without him to distribute the music, whilst everyone always had a cheery word for Billy Wardle, whose ready smile was always evidence on such occasions. Old age and ill-health took him and for the last two years he had to relinquish all active connection with Band affairs, but his epitaph might well read thus: “He did his Job.”

(Faulkner in “WILLIAM WARDLE,” 1938)

William (Billy) Wardle, late of the Boorowa Town and District Band was one of those selfless band members who saw fit to undertake some necessary duties to support the band. That duty being the band librarian, and William Wardle was just one of many band members from bands everywhere who undertook the same role. Despite being untrained as librarians (in the formal understanding of the profession), and amateur, these band librarians organised large quantities of sheet music that the bands owned. They did their part to make sure the band master and each band member had their parts when and where required.

Who were these people, and why did they undertake such an arduous and difficult task? Working largely by themselves, they put their hands up time and time again to do the job, and we can see this in the records of Annual General Meetings that were held by bands. There, in amongst all the other committee positions such as President, Treasurer and Secretary, will be Librarian with the name of the band member (or members) who were elected to this position. Interspersed throughout this post will be lists of band members who were elected as band librarians. The lists are by no means complete as there were so many of them. Names and bands were chosen at random.

This author has some understanding of the role of librarians within community bands being a qualified librarian and having undertaken music librarian roles for bands in the past – the duties of this role in bands has barely changed, albeit for changing technology. This post will try to fit the role of the amateur band librarian within a broader context of music librarianship and librarianship in general. To start this post, we will see where librarianship as a trained profession has come from in Australia, and the very specialised role of music librarians. The next part of this post will unpack the job description of a band librarian, brief and undescriptive as they sometimes were. The third part of this post will highlight the appreciation that was given to band librarians by their bands for undertaking this role.

| 1896 | Sen. Const F. J. Knopp | Hon. Librarian | Sydney Police Band (N.S.W.) |

| 1896 | H. Northe | Librarian | Brighton Brass Band (Vic.) |

| 1897 | Mr. J. Lee | Librarian | Temperance Brass Band (W.A.) |

| 1898 | Mr. F. Morton | Librarian | Lilydale Brass Band (Vic.) |

| 1899 | Mr. Franks | Librarian | Tallangatta Brass Band (Vic.) |

| 1900 | Mr. M. Johnston | Librarian | Lake’s Creek Brass Band (Qld.) |

Librarianship and librarians:

In Australia, the establishment of Universities, Mechanics’ Institutes, schools, and municipal libraries meant that there was a greater need for librarians who understood the rigours of the position. Since the late 1800s, education for librarians in various areas of librarianship has developed consistent with the needs of the profession. Nowadays it is common to find full academic courses for librarians in Universities and TAFE’s. But back in the early days until training began to be more formalised, librarians generally learnt ‘on the job’. In this respect, we could equate this with the early band librarians in Australia who also learnt what to do within the confines of their organisation. There are similarities between the roles of a librarian and amateur band librarian as in general, both organise and catalogue resources. But this is where the similarity ends. This section will outline a brief history of librarianship in Australia and explore the specialised role of a music librarian.

In the library sector and in the band movement, both had the benefit of associations, but it was not always the case. In Australia, as we can see in previous posts, the first band association started forming in the late 1800s and State association started working together in the early 1900s (de Korte, 2018b, 2019a, 2019b). Within the library sector, the first attempts at association began in 1896 with the establishment of a Library Association of Australasia at the conference at The University of Melbourne (Keane, 1982a, 1982b). The Library associations gradually became more focused on the educational needs of librarians (this process took a few decades) as the associations recognized that the profession was changing, and, these associations proactively encouraged librarians to become qualified to do the job (Keane, 1982b). In contrast, the band associations, while representing a largely amateur movement of bands and musicians, at times tried to focus on education and training but unfortunately lacked the resources to do so (de Korte, 2022). Such was the difference between associations that supported professional work, and those that represented amateurs. This is a difference that will be evident throughout this post.

| 1901 | Mr. J. Donelly Mr. H. Wilkinson | Librarian Assistant Librarian | Rutherglen Brass Band (Vic.) |

| 1902 | Mr. F. Raglass | Secretary and Librarian | Narandera Town Band (N.S.W.) |

| 1903 | Mr. W. Symmons | Librarian | Healesville Brass Band (Vic.) |

| 1904 | Mr. E. Schmidt | Librarian | Federal Brass Band (Echuca, Vic.) |

| 1904 | Mr. O. Brauer | Librarian | Petersburg Brass Band (S.A.) |

| 1905 | Mr. Overton | Librarian | Woodend Brass Band (Vic.) |

Music libraries and librarians:

Music Librarians are those that have worked, or currently work in highly specialised positions. They are, as the job title suggests, librarians who work with music resources whether that be sheet music, reference material or recorded music. While special music librarians have been working in this sector in Australia from the early 1900s, professional associations for this sub-sector came much later than regular library associations. The International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres (IAML) was formed in 1949 with an Australian chapter of IAML being formed in 1970 (“Australian Seminar in Music Librarianship,” 1970; Enquist & Flury, 2023).

Music Libraries were first established in Australia in 1913 with the opening of the ‘New South Wales Government Music Library’ which was a library that catered for “societies, church choirs, and other musical bodies” (“The New South Wales Government Music Library,” 1913). It was initially housed at the Sydney Girls’ High School before being moved to the N.S.W. Conservatorium. It is interesting to note that the article published in the Australian Town and Country Journal included a large picture (below) of all the trustees of this library, but no mention of the music librarians.

Like their band librarian counterparts, some music librarians fulfilled roles attached to orchestras and choirs. In 1921 we hear about the passing of Mr. William Henry Gresty who was a Cornet player with Her Majesty’s Theatre Orchestra and in a later career was the Music Librarian with the N.S.W. Conservatorium Orchestra (“DEATH OF LIBRARIAN,” 1921). As it says in his obituary published by The Sun newspaper,

When the Conservatorium was founded he joined the staff as librarian, but kept his position at Her Majesty’s until a couple of years ago when he resigned because of the establishment of the Conservatorium Orchestra as a permanent body. From that time he devoted himself exclusively to the Conservatorium and orchestra, travelling with the latter, and performing an enormous amount of work in looking after the music and the orchestra generally

(“DEATH OF LIBRARIAN,” 1921)

Some years later, the Australian Broadcasting Commission was formed and being the national broadcaster that it was with radio stations around the country, they had a need for music librarians who organised recorded music. One of these music librarians was Mr. Gregory Spencer (pictured below) who was based in Sydney and was the “Federal Records Librarian” (“A.B.C. Librarian,” 1941). No doubt he dealt with music recorded by our brass bands and the A.B.C. Military Band (de Korte, 2018a).

The A.B.C. was also home to several innovations in music librarianship and music copying, including a music copying machine which was invented by their in-house music librarians (“COPYING MACHINE TYPES MUSIC,” 1948).

Just as there were varied roles for librarians, there were also varied roles for music librarians. While fewer in number, their expertise in managing large music-related resources was very much needed at the time – and still is needed. Given some music libraries, like the New South Wales Government Music Library, catered for amateur music groups, it is quite possible that knowledge from the professional music librarians was provided to individuals in these groups with tips on how to manage their music collections. But it is difficult to find some evidence of this happening.

| 1906 | Mr. L. Else | Librarian | Cundletown Brass Band (N.S.W.) |

| 1907 | Mr. S. Lord | Librarian | Kew Brass Band (Vic.) |

| 1908 | Mr. L. Smith | Librarian | Alma Brass Band (N.S.W.) |

| 1909 | Mr. Jewell | Librarian | Borough Brass Band (Clunes, Vic.) |

| 1910 | Messrs. S. Bryant and H. Hoffmann | Librarians | Adelaide City Brass Band (S.A.) |

A vague role description and learning ‘on the job’:

There are dozens of minor details. A library of music has to be formed and maintained. A set of music for an ordinary selection lasting 10 minutes means an expense of from 10’6 to 15’6, and some libraries possess more than 1000 sets. A librarian has to be appointed to look after them.

(Fleming, 1939)

For the newly elected or re-elected librarians of brass bands, doing their duties was sometimes a tough ask. When new music arrived, they had to process and catalogue, stamp, file, and distribute the music to the band members and conductor. Brass band libraries could get quite extensive depending on the activities of the bands. However, there was one main problem. The brass band librarians were often provided with a vague rule on the duty of a librarian, but nothing explaining how to do the job – for some, it was too much. In amongst the sporadic publishing of rules and by-laws of brass bands are some general rules outlining what a librarian should be doing. Some rules were more descriptive than others, such as this rule from the Frankston Brass Band in 1913:

8. The Librarian shall have sole charge of all music of the band. He shall keep a record of name, and shall render to the Secretary annually a statement (or an account) of all music under his charge.

(Plowman et al., 1913)

…which contrasts with the rule provided for the Queanbeyan Town Band librarian in 1915:

40. Librarian’s duties : Charge of music.

(DeClifton & Mathews, 1915)

Rules governing the duties of librarians did not really improve over the years, yet still they carried out their duties. Based on this limited information though, it is quite clear where the librarians stood in chain of command with some rules stating that the librarian must report to the secretary. The Collie Brass Band in Western Australia had a rule that closely matched the rule from the Frankston Brass Band:

22. The Librarian shall take charge of all the music and shall keep correct list of names to tally with Secretary’s.

(“REVISED RULES.,” 1924)

Obviously, some bands provide better job descriptions for librarians in their rules than others. Perhaps this indicates a general envisioning in the band movement of what a band librarian should be doing, but there is no way of knowing this without some very in-depth research. The Peterborough Federal Band from South Australia was one band that did provide a very good rule for the librarian which no doubt helped them in their duties:

13. The Librarian shall take charge of, be responsible for, and keep a catalogue of all music the property of the Band; and distribute and collect the music at practices, concerts, and engagements. He shall furnish a written report of the state of the library at each annual meeting, and must adhere to By-law 21 (b).

(“Peterborough Federal Band,” 1931)

The band member who was elected to be Librarian at the Peterborough Federal Band in 1931 was a Mr. T. Jenkins (“Peterborough Federal Band,” 1931).

It must be said that these band members were used to working under all sorts of rules, by-laws and other regulations – we saw as much in a previous post on the deportment of band members (de Korte, 2021). So having minimal direction on the operating of a large music library was an issue that they dealt with as best they could. Occasionally there were some from this time who found they did not have enough time to undertake the role. In an article published by the Dimboola Banner and Wimmera Mallee Advertiser newspaper in January 1914, Mr. Moy of the Dimboola and District Brass Band submitted his resignation to the band from his post as librarian which was read out at the Annual General Meeting.

The secretary read a letter from Mr Moy, in which he tendered his resignation of the post of librarian.

Mr Moy said that it was a farce for him to continue to hold the position, as he could not find enough time to attend to his duties. He moved that Mr C. Deneys be appointed. After several other members had been nominated and had refused the appointment, Mr Deneys consented to take it, and Mr L. Frazer was elected as his assistant.

(“Dimboola Brass Band.,” 1914)

The position was obviously not for everyone.

Regarding the passing of knowledge from one band librarian to another, we can only assume that there was some kind of handover and there might have been contact between individual band librarians from time to time. Unfortunately, the newspaper articles of the time and other material did not delve into these small details. Any word about training for amateurs in this kind of role is non-existent. This is in contrast with their professional counterparts where there is mentions of the training they required to become fully-fledged librarians (“LIBRARIANSHIP DIPLOMA,” 1939; “Record library school opens,” 1945).

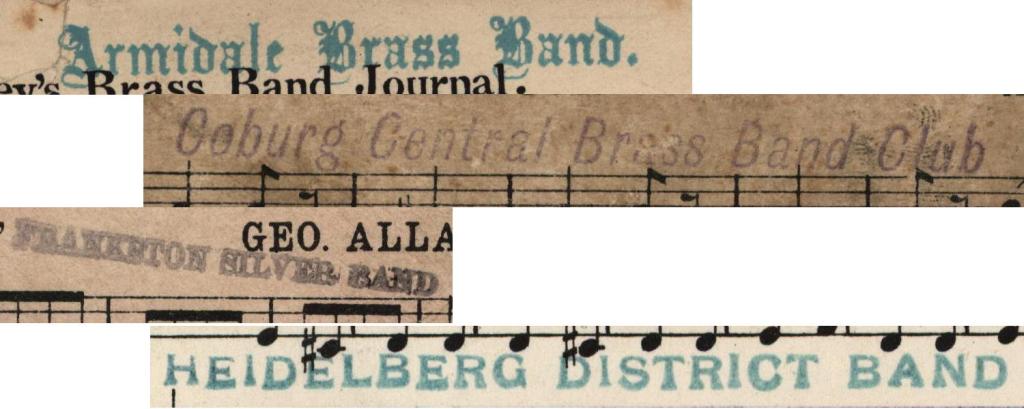

We know what kind of work they did, and it has survived the years. In band libraries all over Australia are collections of music, some decades, or centuries old. Below is a small sample of band stamps that were diligently stamped on every piece of sheet music. Some of the stamps are very old examples, yet they lasted, and we know that a band librarian at some stage was involved in processing this music.

| 1911 | Mr. C. Stewart | Librarian | Derby Brass Band (Tas.) |

| 1912 | Mr. P. Cutter | Librarian | Yea Brass Band (Vic.) |

| 1912 | Mr. D. T. Hobbs | Librarian and property master | Railway Brass Band (W.A.) |

| 1913 | Mr. E. Woolrich Mr. C. Hawkes | Librarian Assistant Librarian | Warburton Brass Band (Vic.) |

| 1914 | Mr. Deneys Mr L. Frazer | Librarian Assistant Librarian | Dimboola and District Brass Band (Vic.) |

| 1915 | Mr. Smallhorn | Librarian | Westonia Brass Band (W.A.) |

| 1915 | Mr. E. Urlwin | Librarian | Balaklava Brass Band (S.A.) |

Always appreciated:

It would be fair to say that a band could not function without a librarian, or two librarians as was the case in some years. As well as their participation as band members, they had these additional tasks to do. We saw at the head of this post the appreciative comments for the late William Wardle of the Boorowa Town and District Band. Every so often there would be another article published in the newspapers about other band librarians who received appreciative comments and presentations from their bands.

In September 1910, the Kew Band in Melbourne awarded their band librarian Mr. Les Smith with a gold medal in appreciation of his services to the band (“Kew Band Presentation.,” 1910). The article published in The Reporter newspaper can be viewed below, and it was obvious that the Kew Band thought very highly of Mr. Smith.

The Murray Bridge Brass Band thought highly of their (former) librarian in 1912 when they placed on a meeting record the “good work done by Mr. W. Paige as librarian to the band, which position is now occupied by Mr. G. Hoare.” (“BAND MATTERS.,” 1912). In Queensland, the Maryborough Naval Band presented their band librarian with gifts for his service. The said person also had other important roles within the band.

During practice at the rooms Lennox street on Thursday night last, the President, Mr. H. A. Reed, sought permission of the Conductor, Mr. W. Ryder, for the Patron, Mr. J. E. Archibald to give a short address to the bandsmen. At the conclusion of the address, a presentation was made to Mr. Vin Zemek (Deputy Band Master, Senior Band and Librarian) of a gold mounted cigarette holder and good supply of cigarettes, for his past untiring efforts in the interest of the band, and his successful work as librarian.

(“NAVAL BAND ASSOCIATION.,” 1919)

It was sometimes necessary for band members to move on from their bands, for whatever reason that may be. At a concert in November 1937, the Mount Gambier Citizens’ Band used the interval to give a presentation and thanks to Euphonium player, committee member, and band librarian Mr. Bern Holman who leaving to take up other activities (“BAND RECITAL.,” 1937).

Sadly, during the First World War, many Australians gave their service and paid the ultimate sacrifice. Private W. C. Carlson of Kapunda, South Australia was one of them and an obituary published in the Kapunda Herald newspaper made mention of his extensive involvement in organisations in the town, including service with the Kapunda Brass Band.

He was an active member of the Kapunda Brass Band, also a member of the local lodge of Rechabites. When the members of the brass band met for practice on Wednesday night Bandmaster Neindorf made feeling references to the death of Private Carlson, who had been an enthusiastic member for a number of years, during which time he acted as librarian. Members sood to order with bowed heads for a time, and then adjourned as a mark of respect for their late comrade.

(“For King and Country,” 1917)

They did their jobs.

| 1916 | Mr. F Rowe Mr. J. Matthews | Librarians | Wandiligong Brass Band (Vic.) |

| 1917 | Mr. H. Little | Librarian | Landsborough Brass Band (Vic.) |

| 1918 | Mr. J. Ormondy | Librarian | Guyra Brass Band (N.S.W.) |

| 1919 | Mr. Wilfred Webster | Librarian | Penguin Brass Band (Tas.) |

| 1920 | Mr. R. Fielder | Librarian | Bayswater Brass Band (Vic.) |

Conclusion:

They worked without the professional knowledge or qualification of a librarian, yet they basically did the same jobs, and organised their band libraries as best they could. In hindsight, would these band librarians have benefited from classes or knowledge from professional librarians? The band movement was very much amateur and as was evident, the crossover of professional knowledge was sporadic at best, even for musical training. Given that early librarians in Australia had limited training themselves, one could only imagine the trials and tribulations of band librarians as they sought to make sense of the role they had to do.

It is through the work of band librarians of the past that we have surviving sets of music that has been neatly catalogued and stamped, ready for future librarians to keep organised. We can see the band stamps in corners of sheet music, the marches that were stuck onto cards, the frail sets of music that were handwritten, and the envelopes and folders to store the music. And if we dig deeply enough, we have their names and bands.

| 1921 | Mr. H. R. Hochuli | Librarian | Magill Brass Band (S.A.) |

| 1922 | Mr. J. Donnelly | Librarian | Skipton Brass Band (Vic.) |

| 1923 | Messrs. W. Stavert and R. Bassman | Librarians | Mullumbimby Citizens’ Band (N.S.W.) |

| 1924 | Mr. Wes Stokes | Librarian | Association Brass Band (Bowral, N.S.W.) |

| 1925 | Mr. A. Clarke | Librarian | Latrobe Federal Brass Band (Tas.) |

| 1926 | Mr. J. Donaldson | Acting Librarian | Kellerberrin Brass Band (W.A.) |

| 1927 | Mr. A. L. Davidson | Secretary and Librarian | Bordertown Brass Band (S.A.) |

| 1928 | Mr. Alf Worrall | Librarian | Victor Harbour Municipal Band (S.A.) |

| 1929 | Mr. R. Ainsworth | Librarian | Wingham Band (N.S.W.) |

| 1930 | Mr. P. Bandt Mr. A. Pedler | Librarian Assistant Librarian | Freeling Brass Band (S.A.) |

References:

ALMA BRASS BAND. (1908, 27 June). Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, NSW : 1888 – 1954), 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article45035483

[Armidale Brass Band]. (n.d.). In S10.4 – Band Stamps (Digital scan of band stamp on sheet music ed., Vol. S10 – Music (Sheet)): Victorian Bands’ League Archive.

ASSOCIATION BRASS BAND. (1924, 27 May). Southern Mail (Bowral, NSW : 1889 – 1954), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article114059676

Australian Seminar in Music Librarianship and Documentation – Adelaide 1970. (1970). [Report]. Australian Journal of Music Education(7), 53-54. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.870190744257826

A.B.C. Librarian. (1941, 18 July). Goulburn Evening Post (NSW : 1940 – 1954), 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103631833

Balaklava Brass Band. (1915, 26 August). Wooroora Producer (Balaklava, SA : 1909 – 1940), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article207099757

BAND MATTERS. (1912, 06 December). Mount Barker Courier and Onkaparinga and Gumeracha Advertiser (SA : 1880 – 1954), 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article147749582

BAND RECITAL : Presentation to Committeeman. (1937, 30 November). Border Watch (Mount Gambier, SA : 1861 – 1954), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article78003653

Bayswater Brass Band. (1920, 17 December). Reporter (Box Hill, Vic. : 1889 – 1925), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article257155681

Bordertown Brass Band. (1927, 24 June). Border Chronicle (Bordertown, SA : 1908 – 1950), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article212866665

BRIGHTON BRASS BAND. (1896, 28 March). Caulfield and Elsternwick Leader (North Brighton, Vic. : 1888 – 1902), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66852240

CITY BRASS BAND. (1910, 02 May). Express and Telegraph (Adelaide, SA : 1867 – 1922), 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article209909713

CLUNES : Brass Band. (1909, 25 February). Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924), 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article217280286

[Coburg Central Brass Band Club]. (n.d.). In S10.4 – Band Stamps (Digital scan of band stamp on sheet music ed., Vol. S10 – Music (Sheet): Victorian Bands’ League Archive.

COPYING MACHINE TYPES MUSIC. (1948, 02 June). Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article22543108

Cundletown Brass Band. (1906, 24 January). Manning River Times and Advocate for the Northern Coast Districts of New South Wales (Taree, NSW : 1898 – 1954), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article172821374

de Korte, J. D. (2018a, 12 July). The A.B.C. Military Band: an ensemble of the times. Band Blasts from the Past : Anecdotes, Stories and Personalities. https://bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2018/07/12/the-a-b-c-military-band-an-ensemble-of-the-times/

de Korte, J. D. (2018b, 15 March). The politics of affiliation: The Victorian Bands’ Association to the Victorian Bands’ League. Band Blasts from the Past : Anecdotes, Stories and Personalities. https://bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2018/03/15/the-politics-of-affiliation-victorian-bands-association-to-the-victorian-bands-league/

de Korte, J. D. (2019a, 07 December). Brass bands of the New South Wales Central West: Part 2: Association and competition. Band Blasts from the Past : Anecdotes, Stories and Personalities. https://bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2019/12/07/brass-bands-of-the-new-south-wales-central-west-part-2-association-and-competition/

de Korte, J. D. (2019b, 05 June). Finding National consensus: how State band associations started working with each other. Band Blasts from the Past : Anecdotes, Stories and Personalities. https://bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2019/06/05/finding-national-consensus-how-state-band-associations-started-working-with-each-other/

de Korte, J. D. (2021, 03 November). Earning points: proper deportment of band member’s. Band Blasts from the Past : Anecdotes, Stories and Personalities. https://bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2021/11/03/earning-points-proper-deportment-of-band-members/

de Korte, J. D. (2022, 04 April). Training Bandmasters in the art of conducting: the problems, the stats quo, and the plans. Band Blasts from the Past : Anecdotes, Stories and Personalities. https://bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2022/04/04/training-bandmasters-in-the-art-of-conducting-the-problems-the-status-quo-and-the-plans/

DEATH OF LIBRARIAN : State Orchestra Official. (1921, 03 June). Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 – 1954), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article221464087

DeClifton, G., & Mathews, F. W. (1915, 18 May). Queanbeyan Town Band. Queanbeyan Age and Queanbeyan Observer (NSW : 1915 – 1927), 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article31665819

DERBY BRASS BAND. (1911, 03 February). Examiner (Launceston, Tas. : 1900 – 1954), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article50459725

Dimboola Brass Band : GENERAL MEETING : WEEKLY PAYMENTS BY MEMBERS TO CEASE : DEPUTY BANDMASTER TO BE APPOINTED : NEW INSTRUMENTS NEEDED. (1914, 23 January). Dimboola Banner and Wimmera and Mallee Advertiser (Vic. : 1914 – 1918), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article152648753

Enquist, I., & Flury, R. (2023). Chronology, 1949-2018. IAML : International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres. Retrieved 14 September 2023 from https://www.iaml.info/iaml-chronology

Federal Brass Band. (1904, 29 January). Riverine Herald (Echuca, Vic. : Moama, NSW : 1869 – 1954; 1998 – 2002), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article115056762

Fleming, A. (1939, 28 May). OUR BANDSMEN PLAY— : To the TUNE of £70,000. Sunday Mail (Brisbane, Qld. : 1926 – 1954), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article98236539

For King and Country : Late Private W. C. Carlson. (1917, 22 June). Kapunda Herald (SA : 1878 – 1951), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article124989226

Fosbrooke, A. R. (1905). Maryborough Naval Volunteer Band, Queensland, 1905 [Photographic print : black & white]. [3234]. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland. https://hdl.handle.net/10462/deriv/248614

[Frankston Silver Band]. (n.d.). In S10.4 – Band Stamps (Digital scan of band stamp on sheet music ed., Vol. S10 – Music (Sheet)): Victorian Bands’ League Archive.

FREELING BRASS BAND. (1930, 27 June). Bunyip (Gawler, SA : 1863 – 1954), 11. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article96669501

GUYRA BRASS BAND. (1918, 09 May). Guyra Argus (NSW : 1902 – 1954), 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article173591348

HEALESVILLE BRASS BAND. (1903, 18 July). Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian (Vic. : 1900 – 1942), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article60284026

[Heidelberg District Band]. (n.d.). In S10.4 – Band Stamps (Digital scan of band stamp on sheet music ed., Vol. S10 – Music (Sheet)): Victorian Bands’ League Archive.

Keane, M. V. (1982a). Chronology of Education for Librarianship in Australia, 1896-1976. The Australian Library Journal, 13(3), 16-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049670.1982.10755458

Keane, M. V. (1982b). The development of education for librarianship in Australia between 1896 and 1976, with special emphasis on the role of the Library Association of Australia. The Australian Library Journal, 31(2), 12-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049670.1982.10755450

Kellerberrin Brass Band. (1926, 15 January). Eastern Recorder (Kellerberrin, WA : 1909 – 1954), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article256404975

Kew Band Presentation. (1910, 30 September). Reporter (Box Hill, Vic. : 1889 – 1925), 7. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article89698013

Kew Brass Band. (1907, 06 September). Reporter (Box Hill, Vic. : 1889 – 1925), 7. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article90312804

LAKE’S CREEK BRASS BAND. (1900, 05 April). Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld. : 1878 – 1954), 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article52571271

LANDSBOROUGH : BRASS BAND. (1917, 01 August). Ballarat Courier (Vic. : 1869 – 1886; 1914 – 1918), 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article73321617

LATROBE BRASS BAND. (1925, 17 September). Daily Telegraph (Launceston, Tas. : 1883 – 1928), 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article153656236

LIBRARIANSHIP DIPLOMA : Establishment Sought. (1939, 28 January). Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), 13. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12091273

LILYDALE BRASS BAND. (1898, 02 December). Lilydale Express and Yarra Glen, Wandin Yallock, Upper Yarra, Healesville and Ringwood Chronicle (Vic. : 1898 – 1914), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article258343462

MAGILL BRASS BAND. (1921, 11 August). Register (Adelaide, SA : 1901 – 1929), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article63195858

[March Card Backing with Victoria Police Band stamp]. (n.d.). In S10.3 – March Card Backs (Digital scan of march card back and band stamp ed., Vol. S10 – Music (Sheet)): Victorian Bands’ League Archive.

MUNICIPAL BAND. (1928, 01 June). Victor Harbor Times and Encounter Bay and Lower Murray Pilot (SA : 1912 – 1930), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article167135026

NAVAL BAND ASSOCIATION : PRESENTATION TO MR. VIN ZEMEK. (1919, 27 May). Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article151041581

The New South Wales Government Music Library–Official Opening by the Minister for Education. (1913, 30 July). Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 – 1919), 27. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article263942420

Norris, A. (1923, 04 October). Mullumbimby Citizens’ Band : ANNUAL REPORT AND BALANCE SHEET. Mullumbimby Star (NSW : 1906 – 1936), 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article125397418

PENGUIN BRASS BAND. (1919, 14 June). Advocate (Burnie, Tas. : 1890 – 1954), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66489853

Peterborough Federal Band. (1924). [Photograph]. [B+27818]. State Library South Australia, Peterborough Collection. https://collections.slsa.sa.gov.au/resource/B+27818

Peterborough Federal Band : Annual General Meeting. (1931, 17 July). Times and Northern Advertiser, Peterborough, South Australia (SA : 1919 – 1950), 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110542695

Petersburg Brass Band. (1904, 19 July). Quorn Mercury (SA : 1895 – 1954), 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article213634359

Plowman, S., Hammond, E. C., Gunson, J. L., & Croskell, V. (1913, 04 October). Rules and Regulations of the Frankston Brass Band. Mornington Standard (Frankston, Vic. : 1911 – 1920), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article65849798

Presto. (1913, 07 February). WARBURTON BRASS BAND. Lilydale Express and Yarra Glen, Wandin Yallock, Upper Yarra, Healesville and Ringwood Chronicle (Vic. : 1898 – 1914), 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article258398095

Railway Brass Band. (1912, 08 June). Northam Advertiser (WA : 1895 – 1955), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article212605209

Record library school opens. (1945, 22 April). Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1931 – 1954), 9. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article248011012

REVISED RULES. (1924, 01 February). Collie Mail (Perth, WA : 1908 – 1954), 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article256075368

Rutherglen Brass Band. (1901, 19 February). Rutherglen Sun and Chiltern Valley Advertiser (Vic. : 1886 – 1957), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article268482585

Skipton Brass Band. (1922, 27 May). Skipton Standard and Streatham Gazette (Vic. : 1914 – 1928), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article269333879

TALLANGATTA BRASS BAND : [FROM THE UPPER MURRAY HERALD]. (1899, 01 April). Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic. : 1855 – 1955), 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article199466692

TEMPERANCE BRASS BAND. (1897, 10 July). Geraldton Murchison Telegraph (WA : 1892 – 1899), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article259398587

The Crown Studios. (1896, 28 March). New South Wales Police Band. Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 – 1919), 20. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71243570

Town Band. (1902, 20 June). Narandera Argus and Riverina Advertiser (NSW : 1893 – 1953), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article99243761

Wandiligong Brass Band. (1916, 17 November). Alpine Observer and North-Eastern Herald (Vic. : 1916 – 1918), 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article129515421

WESTONIA BRASS BAND. (1915, 22 May). Westonian (WA : 1915 – 1920), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article211653459

WILLIAM WARDLE : LATE HONORARY LIBRARIAN OF BOOROWA BAND. (1938, 04 February). Burrowa News (NSW : 1874 – 1951), 8. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article102498287

WINGHAM BAND. (1929, 10 August). Manning River Times and Advocate for the Northern Coast Districts of New South Wales (Taree, NSW : 1898 – 1954), 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article173806266

Woodend Brass Band. (1905, 14 January). Woodend Star (Vic. : 1888 – 1942), 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article270719524

Yea Brass Band. (1912, 14 March). Yea Chronicle (Yea, Vic. : 1891 – 1920), 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article69663903